Gossypol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-Hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-5,5′-di(propan-2-yl)[2,2′-binaphthalene]-8,8′-dicarbaldehyde | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.654 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C30H30O8 | |

| Molar mass | 518.562 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Brown solid |

| Density | 1.4 g/mL |

| Melting point | 177 to 182 °C (351 to 360 °F; 450 to 455 K) (decomposes) |

| Boiling point | 707 °C (1,305 °F; 980 K) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H351 | |

| P201, P202, P281, P308+P313, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

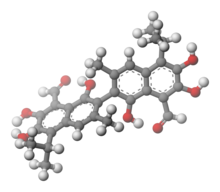

Gossypol (/ˈɡɒsəpɒl/) is a natural phenol derived from the cotton plant (genus Gossypium). Gossypol is a phenolic aldehyde that permeates cells and acts as an inhibitor for several dehydrogenase enzymes. It is a yellow pigment. The structure exhibits atropisomerism, with the two enantiomers having different biochemical properties.[1]

Among other applications, it has been tested as a male oral contraceptive in China. In addition to its putative contraceptive properties, gossypol has also long been known to possess antimalarial properties.[2]

History

[edit]Utilization of cotton-seed oil in the 19th century was complicated by the fact that it stained everything. In 1882-1883 James Longmore from Liverpool took several patents on separating the colorant by partial saponification of the oil,[3][4] and in 1886 he presented his findings to the local section of the Society of Chemical Industry.[5] He is often considered the discoverer of gossypol, even though he only isolated it in crude form.[6]

The name was coined in 1899 by Leon Marchlewski, who first purified the compound and studied some of its chemical properties.[7] F. E. Withers and F. E. Caruth first attributed the toxic properties of the cotton seed (known since the 19th c.) to gossypol in 1915,[8] and its chemical formula was established in 1927 by Earl Perry Clark (1892-1943).[9]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Gossypol is a terpenoid aldehyde which is formed metabolically through acetate via the isoprenoid pathway.[10] The sesquiterpene dimer undergoes a radical coupling reaction to form gossypol.[11] The biosynthesis begins when geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) are combined to make the sesquiterpene precursor farnesyl diphosphate (FPP). The cadinyl cation (1) is oxidized to 2 by (+)-δ-cadinene synthase. The (+)-δ-cadinene (2) is involved in making the basic aromatic sesquiterpene unit, homigossypol, by oxidation, which generates the 3 (8-hydroxy-δ-cadinene) with the help of (+)-δ-cadinene 8-hyroxylase. Compound 3 goes through various oxidative processes to make 4 (deoxyhemigossypol), which is oxidized by one electron into hemigossypol (5, 6, 7) and then undergoes a phenolic oxidative coupling, ortho to the phenol groups, to form gossypol (8).[12] The coupling is catalyzed by a hydrogen peroxide-dependent peroxidase enzyme, which results in the final product.[12]

Research

[edit]Contraception

[edit]A 1929 investigation in Jiangxi showed correlation between low fertility in males and use of crude cottonseed oil for cooking. The compound causing the contraceptive effect was determined to be gossypol.[13] In the 1970s, the Chinese government began researching the use of gossypol as a contraceptive. Their studies involved over 10,000 subjects, and continued for over a decade. They concluded that gossypol provided reliable contraception, could be taken orally as a tablet, and did not upset men's balance of hormones.

However, gossypol also had serious flaws. The studies also discovered an abnormally high rate (0.75%) of hypokalemia (low blood potassium levels) among subjects.[13][14] Hypokalemia causes symptoms of fatigue, muscle weakness, and at its most extreme, paralysis. In addition, about 7% of subjects reported effects on their digestive systems,[13] about 12% had increased fatigue, some subjects experienced impotence or reduced libido, and 9.9% became irreversibly infertile, apparently associated with longer treatment and greater total dose of gossypol.[13] Most subjects recovered after stopping treatment and taking potassium supplements. The same study showed taking potassium supplements during gossypol treatment did not prevent hypokalemia in primates.[14] The potassium deficiency may also be a result of the Chinese diet or genetic predisposition.[14]

In the mid-1990s, the Brazilian pharmaceutical company Hebron announced plans to market a low-dose gossypol pill called Nofertil, but the pill never came to market. Its release was indefinitely postponed due to unacceptably high rates of permanent infertility.[citation needed] 5% to 25% of the men remained azoospermic up to a year after stopping treatment.[14]

Researchers have suggested gossypol might make a good noninvasive alternative to surgical vasectomy.[15]

In 1986, in conjunction with the Chinese Ministry of Public Health and the Rockefeller Foundation, the World Health Organization formalized a decision to discontinue research into gossypol as a male contraceptive drug.[16] In addition to the other side effects, the WHO researchers were concerned about gossypol's toxicity: the LD50 in primates is less than 10 times the contraceptive dose,[14] creating a small therapeutic window. This report effectively ended further studies of gossypol as a temporary contraceptive, but research into using it as an alternative to vasectomy continues in Austria, Brazil, Chile, China, the Dominican Republic, and Nigeria.

Toxicity

[edit]Food and animal agricultural industries must manage cotton-derivative product levels to avoid toxicity. For example, only ruminant microflora can digest gossypol, and then only to a certain level, and cottonseed oil must be refined. Genetically engineered cotton plants that contain little gossypol in the seed may still contain the compound in the stems and leaves.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Beise, Chase L.; Dowd, Michael K.; Reilly, Peter J. (2005). "Conformational analysis of gossypol and its derivatives by molecular mechanics". Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM. 730 (1–3): 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.theochem.2005.05.010.

- ^ Dodou, Kalliopi (2005-10-28). "Investigations on gossypol: past and present developments". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 14 (11): 1419–1434. doi:10.1517/13543784.14.11.1419. ISSN 1354-3784. PMID 16255680. S2CID 32120983.

- ^ Patents for Inventions. Abridgments of Specifications. 1893.

- ^ Reports of Patent, Design, and Trade Mark Cases. Published at the Patent Office Sales Branch. 1892.

- ^ Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry. Society of Chemical Industry. 1886.

- ^ Wang, Xi; Howell, Cheryl Page; Chen, Feng; Yin, Juanjuan; Jiang, Yueming (2009), "Chapter 6 Gossypol-A Polyphenolic Compound from Cotton Plant", Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, vol. 58, Academic Press, pp. 215–263, retrieved 2024-11-24

- ^ Marchlewski, L. (1899-12-07). "Gossypol, ein Bestandtheil der Baumwollsamen". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 60 (1): 84–90. doi:10.1002/prac.18990600108. ISSN 0021-8383.

- ^ Withers, W. A.; Carruth, F. E. (1915-02-26). "Gossypol—A Toxic Substance in Cottonseed. A Preliminary Note". Science. 41 (1052): 324–324. doi:10.1126/science.41.1052.324.b. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Clark, E. P. (1927-12-01). "STUDIES ON GOSSYPOL: I. THE PREPARATION, PURIFICATION, AND SOME OF THE PROPERTIES OF GOSSYPOL, THE TOXIC PRINCIPLE OF COTTONSEED". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 75 (3): 725–739. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)84141-2. ISSN 0021-9258.

- ^ Burgos, M.; Ito, S.; Segal, J. S.; Tran, T. P. (1997). "Effect of Gossypol on Ultrastructure of Spisula Sperm". The Biological Bulletin. 193 (2): 228–229. doi:10.1086/BBLv193n2p228. PMID 28575607.

- ^ Heinstein, P. F.; Herman, L. D.; Tove, B. S.; Smith, H. F. (1970). "Biosynthesis of Gossypol". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 245 (18): 4658–4665. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62845-5. PMID 4318479.

- ^ a b Dewick, P. M. (2008). Medicinal Natural Product: A Biosynthetic Approach (PDF) (3rd ed.). ISBN 978-0-470-74167-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d YU, ZONG-HAN; CHAN, HSIAO CHANG (1998). "Gossypol as a male antifertility agent - why studies should have been continued". International Journal of Andrology. 21 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00091.x. ISSN 0105-6263. PMID 9639145.

- ^ a b c d e "Gossypol". Malecontraceptives.org. 2011-07-27. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18.

- ^ Coutinho, F. M. (2002). "Gossypol: a contraceptive for men". Contraception. 65 (4): 259–263. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00294-9. PMID 12020773.

- ^ Waites, G. M. H.; Wang, C.; Griffin, P. D. (1998). "Gossypol: Reasons for its failure to be accepted as a safe, reversible male antifertility drug". Point of View Review. International Journal of Andrology. 21 (1) (published April 1998): 8–12. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00092.x. ISSN 0105-6263. PMID 9639146.

- ^ "Seeding Hope for Millions". Texas A&M Today. 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

External links

[edit] Media related to Gossypol at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gossypol at Wikimedia Commons