Chromosphere

A chromosphere ("sphere of color", from the Ancient Greek words χρῶμα (khrôma) 'color' and σφαῖρα (sphaîra) 'sphere') is the second layer of a star's atmosphere, located above the photosphere and below the solar transition region and corona. The term usually refers to the Sun's chromosphere, but not exclusively, since it also refers to the corresponding layer of a stellar atmosphere. The name was suggested by the English astronomer Norman Lockyer after conducting systematic solar observations in order to distinguish the layer from the white-light emitting photosphere[1][2].

In the Sun's atmosphere, the chromosphere is roughly 3,000 to 5,000 kilometers (1,900 to 3,100 miles) in height, or slightly more than 1% of the Sun's radius at maximum thickness. It possesses a homogeneous layer at the boundary with the photosphere. Narrow jets of plasma, called spicules, rise from this homogeneous region and through the chromosphere, extending up to 10,000 km (6,200 mi) into the corona above.

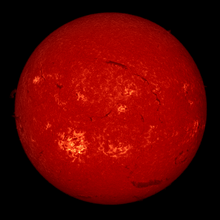

The chromosphere has a characteristic red color due to electromagnetic emissions in the Hα spectral line. Information about the chromosphere is primarily obtained by analysis of its emitted electromagnetic radiation.[3] The chromosphere is also visible in the light emitted by ionized calcium, Ca II, in the violet part of the solar spectrum at a wavelength of 393.4 nanometers (the Calcium K-line).[4]

Chromospheres have also been observed on stars other than the Sun.[5] On large stars, chromospheres sometimes make up a significant proportion of the entire star. For example, the chromosphere of supergiant star Antares has been found to be about 2.5 times larger in thickness than the star's radius.[6]

Physical properties

[edit]

The density of the Sun's chromosphere decreases exponentially with distance from the center of the Sun by a factor of roughly 10 million, from about 2×10−4 kg/m3 at the chromosphere's inner boundary to under 1.6×10−11 kg/m3 at the outer boundary.[7] The temperature initially decreases from the inner boundary at about 6000 K[8] to a minimum of approximately 3800 K,[9] but then increasing to upwards of 35,000 K[8] at the outer boundary with the transition layer of the corona (see Stellar corona § Coronal heating problem).

The density of the chromosphere is 10−4 times that of the underlying photosphere and 10−8 times that of the Earth's atmosphere at sea level. This makes the chromosphere normally invisible and it can be seen only during a total eclipse, where its reddish colour is revealed. The colour hues are anywhere between pink and red.[10] Without special equipment, the chromosphere cannot normally be seen due to the overwhelming brightness of the photosphere.

The chromosphere's spectrum is dominated by emission lines when observed at the solar limb.[11][12] In particular, one of its strongest lines is the Hα at a wavelength of 656.3 nm; this line is emitted by a hydrogen atom whenever its electron makes a transition from the n=3 to the n=2 energy level. A wavelength of 656.3 nm is in the red part of the spectrum, which causes the chromosphere to have a characteristic reddish colour.

Phenomena

[edit]

Many different phenomena can be observed in chromospheres.

Plage

[edit]A plage is a particularly bright region within stellar chromospheres, which are often associated with magnetic activity.[13]

Spicules

[edit]The most commonly identified feature in the solar chromosphere are spicules. Spicules rise to the top of the chromosphere and then sink back down again over the course of about 10 minutes.[14]

Oscillations

[edit]Since the first observations with the instrument SUMER on board SOHO, periodic oscillations in the solar chromosphere have been found with a frequency from 3 mHz to 10 mHz, corresponding to a characteristic periodic time of three minutes.[15] Oscillations of the radial component of the plasma velocity are typical of the high chromosphere. The photospheric granulation pattern usually has no oscillations above 20 mHz; however, higher frequency waves (100 mHz, or a 10 s period) were detected in the solar atmosphere (at temperatures typical of the transition region and corona) by TRACE.[16]

Loops

[edit]Plasma loops can be seen at the border of the solar disk in the chromosphere. They are different from solar prominences because they are concentric arches with maximum temperature of the order 0.1 MK (too low to be considered coronal features). These cool-temperature loops show an intense variability: they appear and disappear in some UV lines in a time less than an hour, or they rapidly expand in 10–20 minutes. Foukal[17] studied these cool loops in detail from the observations taken with the EUV spectrometer on Skylab in 1976. When the plasma temperature of these loops becomes coronal (above 1 MK), these features appear more stable and evolve over longer times.

Network

[edit]Images taken in typical chromospheric lines show the presence of brighter cells, usually referred to as the network, while the surrounding darker regions are named internetwork. They look similar to granules commonly observed on the photosphere due to the heat convection.

On other stars

[edit]Chromospheres are present on almost all luminous stars other than white dwarfs. They are most prominent and magnetically active on lower-main sequence stars, on brown dwarfs of F and later spectral types, and on giant and subgiant stars.[13]

A spectroscopic measure of chromospheric activity on other stars is the Mount Wilson S-index.[18][19]

See also

[edit]- Orders of magnitude (density) – Mass per unit volume

- Moreton wave – Large-scale chromospheric perturbation

References

[edit]- ^ "II. Spectroscopic observation of the sun, No. II., was resumed and concluded". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 17: 131–132. 1869-12-31. doi:10.1098/rspl.1868.0019. ISSN 0370-1662.

- ^ Lockyer, J. Norman (1868-01-01). "Spectroscopic Observation of the Sun, No. II". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series I. 17: 131–132. Bibcode:1868RSPS...17..131L.

- ^ Jess, D.B; Morton, RJ; Verth, G; Fedun, V; Grant, S.T.D; Gigiozis, I. (July 2015). "Multiwavelength Studies of MHD Waves in the Solar Chromosphere". Space Science Reviews. 190 (1–4): 103–161. arXiv:1503.01769. Bibcode:2015SSRv..190..103J. doi:10.1007/s11214-015-0141-3. S2CID 55909887.

- ^ [1]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The Chromosphere". Archived from the original on 2014-04-04. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ^ "Supergiant Atmosphere of Antares Revealed by Radio Telescopes". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Kontar, E. P.; Hannah, I. G.; Mackinnon, A. L. (2008), "Chromospheric magnetic field and density structure measurements using hard X-rays in a flaring coronal loop", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 489 (3): L57, arXiv:0808.3334, Bibcode:2008A&A...489L..57K, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810719, S2CID 1651161

- ^ a b "SP-402 A New Sun: The Solar Results From Skylab". Archived from the original on 2004-11-18.

- ^ Avrett, E. H. (2003), "The Solar Temperature Minimum and Chromosphere", ASP Conference Series, 286: 419, Bibcode:2003ASPC..286..419A, ISBN 978-1-58381-129-0

- ^ Freedman, R. A.; Kaufmann III, W. J. (2008). Universe. New York, USA: W. H. Freeman and Co. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-7167-8584-2.

- ^ Carlsson, Mats; Pontieu, Bart De; Hansteen, Viggo H. (2019-08-18). "New View of the Solar Chromosphere". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 57 (Volume 57, 2019): 189–226. Bibcode:2019ARA&A..57..189C. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-052044. ISSN 0066-4146.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Solanki, Sami K. (June 2004). "Structure of the solar chromosphere". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 2004 (IAUS223): 195–202. Bibcode:2004IAUS..223..195S. doi:10.1017/S1743921304005587. ISSN 1743-9213.

- ^ a b de Grijs, Richard; Kamath, Devika (15 November 2021). "Stellar Chromospheric Variability". Universe. 7 (11): 440. Bibcode:2021Univ....7..440D. doi:10.3390/universe7110440.

- ^ Wilkinson, John (2012). New eyes on the sun : a guide to satellite images and amateur observation. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-22839-1. OCLC 773089685.

- ^ Carlsson, M.; Judge, P.; Wilhelm, K. (1997). "SUMER Observations Confirm the Dynamic Nature of the Quiet Solar Outer Atmosphere: The Internetwork Chromosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 486 (1): L63. arXiv:astro-ph/9706226. Bibcode:1997ApJ...486L..63C. doi:10.1086/310836. S2CID 119101577.

- ^ De Forest, C.E. (2004). "High-Frequency Waves Detected in the Solar Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): L89. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617L..89D. doi:10.1086/427181.

- ^ Foukal, P.V. (1976). "The pressure and energy balance of the cool corona over sunspots". The Astrophysical Journal. 210: 575. Bibcode:1976ApJ...210..575F. doi:10.1086/154862.

- ^ Karoff, Christoffer; Knudsen, Mads Faurschou; De Cat, Peter; Bonanno, Alfio; Fogtmann-Schulz, Alexandra; Fu, Jianning; Frasca, Antonio; Inceoglu, Fadil; Olsen, Jesper; Zhang, Yong; Hou, Yonghui; Wang, Yuefei; Shi, Jianrong; Zhang, Wei (March 24, 2016). "Observational evidence for enhanced magnetic activity of superflare stars". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11058. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711058K. doi:10.1038/ncomms11058. PMC 4820840. PMID 27009381.

- ^ upload/k habconf2016/pdf/poster/Mengel.pdf A small survey of the magnetic fields of planet-hosting stars (upload/k habconf2016/pdf/poster/Mengel.pdf Archived 2016-12-22 at the Wayback Machine) gives "Wright J. T., Marcy G. W., Butler R. P., Vogt S. S., 2004, ApJS, 152, 261" as a ref for s-index.

External links

[edit]- Animated explanation of the Chromosphere (and Transition Region) Archived 2015-11-16 at the Wayback Machine (University of South Wales).