Kurt Cobain

Kurt Cobain | |

|---|---|

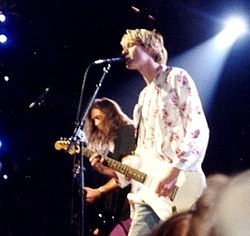

Cobain with Nirvana in 1992 | |

| Born | February 20, 1967 Aberdeen, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | c. April 5, 1994 (aged 27) Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Body discovered | April 8, 1994 |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | Frances Bean Cobain |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1985–1994 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Signature | |

| |

Kurt Donald Cobain (February 20, 1967 – c. April 5, 1994) was an American musician. He was the lead vocalist, guitarist, primary songwriter, and a founding member of the grunge band Nirvana. Through his angsty songwriting and anti-establishment persona, his compositions widened the thematic conventions of mainstream rock music. He was heralded as a spokesman of Generation X, and is widely recognized as one of the most influential rock musicians.

Cobain formed Nirvana with Krist Novoselic and Aaron Burckhard in 1987, establishing themselves as part of the Seattle music scene that later became known as grunge. Burckhard was replaced by Chad Channing before the band released their debut album Bleach (1989) on Sub Pop, after which Channing was in turn replaced by Dave Grohl. With this finalized lineup, the band signed with DGC and found commercial success with the single "Smells Like Teen Spirit" from their critically acclaimed second album Nevermind (1991). Cobain wrote many other hit Nirvana songs such as "Come as You Are", "Lithium", "In Bloom", "Heart-Shaped Box", and "Something in the Way".[1][2] Although he was hailed as the voice of his generation following Nirvana's sudden success, he was uncomfortable with this role.[3]

During his final years, Cobain struggled with a heroin addiction, stomach pain, and chronic depression.[4] He also struggled with the personal and professional pressures of fame, and was often in the spotlight for his tumultuous marriage to fellow musician Courtney Love, with whom he had a daughter named Frances.[5] In March 1994, he overdosed on a combination of champagne and Rohypnol, subsequently undergoing an intervention and detox program. On April 8, 1994, he was found dead in the greenhouse of his Seattle home at the age of 27,[6] with police concluding that he had died around three days earlier from a self-inflicted shotgun wound to the head.[7]

Cobain was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, alongside Nirvana bandmates Novoselic and Grohl, in their first year of eligibility in 2014. Rolling Stone included him on its lists of the 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time, 100 Greatest Guitarists, and 100 Greatest Singers of All Time.[8] He was ranked 7th by MTV in the "22 Greatest Voices in Music", and was placed 20th by Hit Parader on their 2006 list of the "100 Greatest Metal Singers of All Time".

Early life

Kurt Donald Cobain was born at Grays Harbor Hospital in Aberdeen, Washington, on February 20, 1967,[9] the son of waitress Wendy Elizabeth (née Fradenburg; 1947-2021) and car mechanic Donald Leland Cobain (born 1946).[10] His parents married in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, on July 31, 1965. Cobain had Dutch, English, French, German, Irish, and Scottish ancestry.[11]: 13 [12][13]: 7 The Cobain surname comes from his Irish ancestors, who emigrated in 1875 from Carrickmore, a village near Omagh in County Tyrone in Ulster, the northern province in Ireland.[13]: 7 Researchers found that they were shoemakers, originally surnamed Cobane, and were Ulster Scots people who came from the Inishatieve area of Carrickmore. They first settled in Canada, where they lived in Cornwall, Ontario, before moving to Washington.[14] Cobain mistakenly believed that his Irish ancestors came from County Cork.[15] His younger sister, Kimberly, was born on April 24, 1970.[10][12]

Cobain's family had a musical background. His maternal uncle, Chuck Fradenburg, played in a band called the Beachcombers; his aunt, Mari Earle, played guitar and performed in bands throughout Grays Harbor County; and his great-uncle, Delbert, had a career as an Irish tenor, making an appearance in the 1930 film King of Jazz. Kurt was described as a happy and excitable child, who also exhibited sensitivity and care. His talent as an artist was evident from an early age, as he would draw his favorite characters from films and cartoons, such as the Creature from the Black Lagoon and Donald Duck, in his bedroom.[9][13]: 11 He was encouraged by his grandmother, Iris Cobain, a professional artist.[16] Cobain developed an interest in music at a young age. According to his aunt Mari, he began singing at the age of two. At age four, he started playing the piano and singing, writing a song about a trip to a park. He listened to artists including Electric Light Orchestra (ELO),[17] and, from a young age, would sing songs including Arlo Guthrie's "Motorcycle Song", the Beatles' "Hey Jude", Terry Jacks' "Seasons in the Sun", and the theme song to the Monkees television show.[13]: 9

When Cobain was nine years old, his parents divorced.[13]: 20 He later said the divorce had a profound effect on his life, and his mother noted that his personality changed dramatically; Cobain became defiant and withdrawn.[11]: 17 In a 1993 interview, he said he felt "ashamed" of his parents as a child and had desperately wanted to have a "typical family ... I wanted that security, so I resented my parents for quite a few years because of that."[18] His parents found new partners after the divorce. Although his father had promised not to remarry, he married Jenny Westeby, to Kurt's dismay.[13]: 24 Cobain, his father, Westeby, and her two children, Mindy and James, moved into a new household. Cobain liked Westeby at first, as she gave him the maternal attention he desired.[13]: 25 In January 1979, Westeby gave birth to a boy, Chad Cobain.[13]: 24 This new family, which Cobain insisted was not his real one, was in stark contrast to the attention Cobain was used to receiving as an only boy, and he became resentful of his stepmother.[13]: 24, 25 Cobain's mother dated a man who was abusive; Cobain witnessed the domestic violence inflicted upon her, with one incident resulting in her being hospitalized with a broken arm.[13]: 25, 26 Wendy refused to press charges, remaining committed to the relationship.[13]: 26

Cobain behaved insolently toward adults during this period and began bullying another boy at school. His father and Westeby took him to a therapist who concluded that he would benefit from a single-family environment.[13]: 26 Both sides of the family unsuccessfully attempted to reunite his parents. On June 28, 1979, Cobain's mother granted full custody to his father.[13]: 27 Cobain's teenage rebellion quickly became overwhelming for his father who placed him in the care of family and friends. While living with the born-again Christian family of his friend Jesse Reed, Cobain became a devout Christian and attended church services regularly. He later renounced Christianity, engaging in what was described as "anti-God" rants. Kurt claimed that "Lithium" was about his experience while living with the Reed family. He also stated in a 1992 interview that it was a fictionalized account of a man who "turned to religion as a last resort to keep himself alive" after the death of his girlfriend, "to keep him from suicide".[19] However, spirituality remained an important part of Cobain's personal life and beliefs.[11]: 22 [13]: 196 [13]: 69

Although uninterested in sports, Cobain was enrolled in a junior high school wrestling team at the insistence of his father. He was a skilled wrestler but despised the experience. Because of the ridicule he endured from his teammates and coach, he allowed himself to be pinned in an attempt to sadden his father. Later, his father enlisted him in a Little League Baseball team, where Cobain would intentionally strike out to avoid playing.[11]: 20–25 Cobain befriended a gay student at school and was bullied by peers who concluded that he was gay. In an interview, he said that he liked being associated with a gay identity because he did not like people, and when they thought he was gay they left him alone. He said, "I started being really proud of the fact that I was gay even though I wasn't." Cobain backed away in an occasion where this friend tried to kiss him, explaining to his friend that he was not gay, though they remained friends. According to Cobain, he used to spray paint "God Is Gay" on pickup trucks in the Aberdeen area. Police records show that Cobain was arrested for spray painting the phrase "ain't got no how watchamacallit" on vehicles.[13]: 68

Cobain often drew during classes. When given a caricature assignment for an art course, Cobain drew Michael Jackson but was told by the teacher that the image was inappropriate for a school hallway. He then drew an image of then-President Ronald Reagan that was seen as "unflattering".[13]: 41 Through art and electronics classes, Cobain met Roger "Buzz" Osborne, singer and guitarist of the Melvins, who became his friend and introduced him to punk rock and hardcore music.[20]: 35, 36 [21] As attested to by several of Cobain's classmates and family members, the first concert he attended was Sammy Hagar and Quarterflash, held at the Seattle Center Coliseum in 1983.[9][13]: 44 Cobain, however, claimed that the first live show he attended was the Melvins, when they played a free concert outside the Thriftway supermarket where Osborne worked. Cobain wrote in his journals of this experience, as well as in interviews, singling out the impact it had on him.[13]: 45 [22] As a teenager living in Montesano, Washington, Cobain eventually found escape through the thriving Pacific Northwest punk scene, going to punk rock shows in Seattle.[11]

During his second year in high school, Cobain began living with his mother in Aberdeen. Two weeks prior to graduation, he dropped out of Aberdeen High School upon realizing that he did not have enough credits to graduate. His mother gave him an ultimatum: find employment or leave. After one week, Cobain found his clothes and other belongings packed away in boxes.[11]: 35 Feeling banished, Cobain stayed with friends, occasionally sneaking back into his mother's basement.[11]: 37 Cobain also claimed that, during periods of homelessness, he lived under a bridge over the Wishkah River,[11]: 37 an experience that inspired the song "Something in the Way". His future bandmate Krist Novoselic later said, "He hung out there, but you couldn't live on those muddy banks, with the tides coming up and down. That was his own revisionism."[23] In late 1986, Cobain moved into an apartment, paying his rent by working at the Polynesian Resort, a themed resort on the Pacific coast at Ocean Shores, Washington approximately 20 miles (32 km) west of Aberdeen.[11]: 43 During this period, he traveled frequently to Olympia, Washington, to go to rock concerts.[11]: 46 During his visits to Olympia, Cobain formed a relationship with Tracy Marander. Their relationship was close but strained by financial problems and Cobain's absence when touring. Marander supported the couple by working at the cafeteria of the Boeing plant in Auburn, Washington, often stealing food. Cobain spent most of his time sleeping into the late evening, watching television, and concentrating on art projects.

Marander's insistence that he get a job caused arguments that influenced Cobain to write the song "About a Girl", which appeared on the Nirvana album Bleach. Marander is credited with having taken the cover photo for the album, as well as the front and back cover photos of their Blew single. She did not become aware that Cobain wrote "About a Girl" about her until years after his death.[13]: 88–93, 116–117, 122, 134–136, 143, 153 Soon after his separation from Marander, Cobain began dating Tobi Vail, an influential punk zinester of the riot grrrl band Bikini Kill who embraced the DIY ethos. After meeting Vail, Cobain vomited, overwhelmed with anxiety caused by his infatuation with her. This event inspired the lyric "love you so much it makes me sick" in the song "Aneurysm".[13]: 152 While Cobain regarded Vail as his female counterpart, his relationship with her waned; he desired the maternal comfort of a traditional relationship, which Vail regarded as sexist within a countercultural punk rock community. Vail's lovers were described by her friend Alice Wheeler as "fashion accessories".[13]: 153 Cobain wrote many of his songs about Vail.[13]

Career

Early musical projects

On his 14th birthday, February 20, 1981, Cobain's uncle offered him the choice of either a bike or a used guitar; Kurt chose the guitar. Soon, he was trying to play Led Zeppelin's song "Stairway to Heaven". He also learned how to play "Louie Louie", Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust", and the Cars' "My Best Friend's Girl", before he began working on his own songs. Cobain played left-handed, despite being forced to write right-handed.[11]: 22

In early 1985, Cobain formed Fecal Matter after he had dropped out of Aberdeen High School.[20] One of "several joke bands" that arose from the circle of friends associated with the Melvins,[20] it initially featured Cobain singing and playing guitar, Melvins drummer Dale Crover playing bass, and Greg Hokanson playing drums.[24] They spent several months rehearsing original material and covers, including songs by the Ramones, Led Zeppelin, and Jimi Hendrix.[20][25]

Nirvana

During high school, Cobain rarely found anyone with whom he could play music. While hanging out at the Melvins' practice space, he met Krist Novoselic, a fellow devotee of punk rock. Novoselic's mother owned a hair salon, and the pair occasionally practiced in the upstairs room of the salon. A few years later, Cobain tried to convince Novoselic to form a band with him by lending him a copy of a home demo recorded by Fecal Matter.[11] After months of asking, Novoselic agreed to join Cobain, forming the beginnings of Nirvana.[11]: 45 Religion appeared to remain a significant muse to Cobain during this time as he often used Christian imagery in his work and developed an interest in Jainism and Buddhist philosophy.

Cobain became disenchanted after early touring because of the band's inability to draw substantial crowds and the difficulty in supporting themselves financially. During their first few years playing together, Novoselic and Cobain were hosts to a succession of drummers. Eventually, the band settled on Chad Channing with whom Nirvana recorded the album Bleach, released on Sub Pop Records in 1989. Cobain, however, became dissatisfied with Channing's style and subsequently fired him. He and Novoselic eventually hired Dave Grohl to replace Channing. Grohl helped the band record their 1991 major-label debut, Nevermind. With Nevermind's lead single, "Smells Like Teen Spirit", Nirvana quickly entered the mainstream, popularizing a subgenre of alternative rock called "grunge". Since their debut, Nirvana has sold over 28 million albums in the United States alone and over 75 million worldwide.[26][27] The success of Nevermind provided numerous Seattle bands, such as Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden, access to wider audiences. As a result, alternative rock became a dominant genre on radio and music television in the U.S. during the first half of the 1990s. Nirvana was considered the "flagship band of Generation X", and Cobain found himself reluctantly anointed by the media as the generation's "spokesman".[28] He resented this characterization since he believed his artistic message had been misinterpreted by the public.[29]

When you're in the public eye, you have no choice but to be raped over and over again – they'll take every ounce of blood out of you until you're exhausted. ... I'm looking forward to the future. It will only be another year and then everyone will forget about it.

—Kurt Cobain on the overwhelming media attention after Nevermind, 1992[30]

Cobain struggled to reconcile the massive success of Nirvana with his underground roots and vision. He also felt persecuted by the media, comparing himself to Frances Farmer whom he named a song after.[31] He began to harbor resentment against people who claimed to be fans of the band yet refused to acknowledge, or misinterpreted, the band's social and political views. A vocal opponent of sexism, racism, sexual assault, and homophobia, he was publicly proud that Nirvana had played at a gay rights benefit concert that was held to oppose Oregon's 1992 Ballot Measure 9, which would have directed Oregon schools to teach that homosexuality was "abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse".[32][33] Cobain was a vocal supporter of the pro-choice movement, and Nirvana was involved in L7's Rock for Choice campaign.[34] He received death threats from a small number of anti-abortion activists for participating in the pro-choice campaign, with one activist threatening to shoot Cobain as soon as he stepped on a stage.[13]: 253

Other collaborations

In 1989, members of Nirvana and fellow American alternative rock band Screaming Trees formed a side project known as the Jury. The band featured Cobain on vocals and guitar, Mark Lanegan on vocals, Krist Novoselic on bass, and Mark Pickerel on drums. Over two days of recording sessions, on August 20 and 28, 1989, the band recorded four songs also performed by Lead Belly; "Where Did You Sleep Last Night?", an instrumental version of "Grey Goose", "Ain't It a Shame", and "They Hung Him on a Cross", the latter of which featured Cobain performing solo.[35] Cobain was inspired to record the songs after receiving a copy of Lead Belly's Last Sessions from friend Slim Moon; after hearing it, he "felt a connection to Leadbelly's almost physical expressions of longing and desire."[36]

In 1990, Cobain and his girlfriend, Tobi Vail of the riot grrrl band Bikini Kill, collaborated on a musical project called Bathtub is Real in which they both sang and played guitar and drums. They recorded their songs on a four-track tape machine that belonged to Vail's father. In Everett True's 2009 book Nirvana: The Biography, Vail is quoted as saying that Cobain "would play the songs he was writing, I would play the songs I was writing and we'd record them on my dad's four-track. Sometimes I'd sing on the songs he was writing and play drums on them ... He was really into the fact that I was creative and into music. I don't think he'd ever played music with a girl before. He was super-inspiring and fun to play with."[37] The musician Slim Moon described their sound as "like the minimal quiet pop songs that Olympia is known for. Both of them sang; it was really good."[38]

In 1992, Cobain contacted William S. Burroughs about a possible collaboration. Burroughs responded by sending him a recording of "The Junky's Christmas"[39] (which he recorded in his studio in Lawrence, Kansas).[40] Two months later at a studio in Seattle, Cobain added guitar backing based on "Silent Night" and "To Anacreon in Heaven". The two would meet shortly later in Lawrence, Kansas and produce "The 'Priest' They Called Him", a spoken word version of "The Junky's Christmas".[39][40]

Musical influences

The Beatles were an early and lasting influence on Cobain; his aunt Mari remembers him singing "Hey Jude" at the age of two.[13]: 9 "My aunts would give me Beatles records", Cobain told Jon Savage in 1993, "so for the most part [I listened to] the Beatles [as a child], and if I was lucky, I'd be able to buy a single."[41] Cobain expressed a particular fondness for John Lennon, whom he called his "idol" in his posthumously released journals,[42] and he said that he wrote the song "About a Girl", from Nirvana's 1989 debut album Bleach, after spending three hours listening to Meet the Beatles!.[13]: 121

Cobain was also a fan of 1970s hard rock and heavy metal bands, including Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, Black Sabbath, Aerosmith, Queen, and Kiss. Nirvana occasionally played cover songs by these bands, including Led Zeppelin's "Heartbreaker", "Moby Dick" and "Immigrant Song", Black Sabbath's "Hand of Doom", and Kiss' "Do You Love Me?" and wrote the Incesticide song "Aero Zeppelin" as a tribute to Led Zeppelin and Aerosmith. Recollecting touring with his band, Cobain stated, "I used to take a nap in the van and listen to Queen. Over and over again and drain the battery on the van. We'd be stuck with a dead battery because I'd listened to Queen too much".[43]

He was introduced to punk rock and hardcore music by his Aberdeen classmate Buzz Osborne, lead singer and guitarist of the Melvins, who taught Cobain about punk by loaning him records and old copies of the Detroit-based magazine Creem.[44] Punk rock proved to be a profound influence on a teenaged Cobain's attitude and artistic style. His first punk rock album was Sandinista! by the Clash,[13]: 169 but he became a bigger fan of fellow 1970s British punk band the Sex Pistols, describing them as "one million times more important than the Clash" in his journals.[42] He quickly discovered contemporary American hardcore bands like Black Flag, Bad Brains, Millions of Dead Cops and Flipper.[44] The Melvins themselves were a major early musical influence on Cobain; his admiration for them led him to drive their van on tour and help them to carry their equipment.[20]: 42 [9]: 153 He and Novoselic watched hundreds of Melvins rehearsals and "learned almost everything from them", as stated by Cobain.[45][30] The Melvins' heavy, grungey sound was mimicked by Nirvana on many songs from Bleach; in an early interview given by Nirvana, Cobain stated that their biggest fear was to be perceived as a "Melvins rip-off".[13]: 153 After their commercial success, the members of Nirvana would constantly talk about the Melvins' importance to them in the press.[46][30]

Cobain was an admirer of Jimi Hendrix, and said in reference to the growing media attention on the Seattle scene at the time, "I mean, we had Jimi Hendrix. Heck. What more do we want?".[47] In a 1993 interview Cobain called Hendrix "a great musician and a great composer," and noted that, "I have great respect for him."[48]

Cobain was also a fan of protopunk acts like the Stooges, whose 1973 album Raw Power he listed as his favorite of all time in his journals.[42]

The 1980s American alternative rock band Pixies were instrumental in helping an adult Cobain develop his own songwriting style. In a 1992 interview with Melody Maker, Cobain said that hearing their 1988 debut album, Surfer Rosa, "convinced him to abandon his more Black Flag-influenced songwriting in favor of the Iggy Pop/Aerosmith-type songwriting that appeared on Nevermind.[49] In a 1993 interview with Rolling Stone, he said that "Smells Like Teen Spirit" was his attempt at "trying to rip off the Pixies. I have to admit it. When I heard the Pixies for the first time, I connected with that band so heavily that I should have been in that band—or at least a Pixies cover band. We used their sense of dynamics, being soft and quiet and then loud and hard".[50]

Cobain's appreciation of early alternative rock bands also extended to Sonic Youth and R.E.M., both of which the members of Nirvana befriended and looked up to for advice. It was under recommendation from Sonic Youth's Kim Gordon that Nirvana signed to DGC in 1990,[11]: 162 and both bands did a two-week tour of Europe in the summer of 1991, as documented in the 1992 documentary, 1991: The Year Punk Broke. In 1993, Cobain said of R.E.M.: "If I could write just a couple of songs as good as what they've written... I don't know how that band does what they do. God, they're the greatest. They've dealt with their success like saints, and they keep delivering great music".[50]

After attaining mainstream success, Cobain became a devoted champion of lesser known indie bands, covering songs by the Vaselines, Meat Puppets, Wipers and Fang onstage and/or in the studio, wearing Daniel Johnston T-shirts during photo shoots, having the K Records logo tattooed on his forearm, and enlisting bands like Butthole Surfers, Shonen Knife, Chokebore and Half Japanese along for the In Utero tour in late 1993 and early 1994. Cobain even invited his favorite musicians to perform with him: ex-Germs guitarist Pat Smear joined the band in 1993, and the Meat Puppets appeared onstage during Nirvana's 1993 MTV Unplugged appearance to perform three songs from their second album, Meat Puppets II.[51]

Nirvana's Unplugged set includes renditions of "The Man Who Sold the World", by David Bowie, and the American folk song, "Where Did You Sleep Last Night", as adapted by Lead Belly. Cobain introduced the latter by calling Lead Belly his favorite performer, and in a 1993 interview revealed he had been introduced to him from reading the American author William S. Burroughs, saying: "I remember [Burroughs] saying in an interview, 'These new rock'n'roll kids should just throw away their guitars and listen to something with real soul, like Leadbelly.' I'd never heard about Leadbelly before so I bought a couple of records, and now he turns out to be my absolute favorite of all time in music. I absolutely love it more than any rock'n'roll I ever heard."[52] The album MTV Unplugged in New York was released posthumously in 1994. It has drawn comparisons to R.E.M.'s 1992 release, Automatic for the People.[53] In 1993, Cobain had predicted that the next Nirvana album would be "pretty ethereal, acoustic, like R.E.M.'s last album".[50]

"Yeah, he talked a lot about what direction he was heading in", Cobain's friend, R.E.M.'s lead singer Michael Stipe, told Newsweek in 1994. "I mean, I know what the next Nirvana recording was going to sound like. It was going to be very quiet and acoustic, with lots of stringed instruments. It was going to be an amazing fucking record, and I'm a little bit angry at him for killing himself. He and I were going to record a trial run of the album, a demo tape. It was all set up. He had a plane ticket. He had a car picking him up. And at the last minute he called and said, 'I can't come.'" Stipe was chosen as the godfather of Cobain's and Courtney Love's daughter, Frances Bean Cobain.[54]

Artistry

According to Grohl, Cobain believed that music comes first and lyrics second; he focused primarily on the melodies.[55] He complained when fans and rock journalists attempted to decipher his singing and extract meaning from his lyrics, writing: "Why in the hell do journalists insist on coming up with a second-rate Freudian evaluation of my lyrics, when 90 percent of the time they've transcribed them incorrectly?"[13]: 182 Though Cobain insisted on the subjectivity and unimportance of his lyrics, he labored and procrastinated in writing them, often changing the content and order of lyrics during performances.[13]: 177 Cobain would describe his own lyrics as "a big pile of contradictions. They're split down the middle between very sincere opinions that I have and sarcastic opinions and feelings that I have and sarcastic and hopeful, humorous rebuttals toward cliché bohemian ideals that have been exhausted for years."[56]

Cobain originally wanted Nevermind to be divided into two sides: a "Boy" side, for the songs written about the experiences of his early life and childhood, and a "Girl" side, for the songs written about his dysfunctional relationship with Vail.[13]: 177 Charles R. Cross wrote, "In the four months following their break-up, Kurt would write a half dozen of his most memorable songs, all of them about Tobi Vail." Though Cobain wrote "Lithium" before meeting Vail, he wrote the lyrics to reference her.[13]: 168–169 Cobain said in an interview with Musician that he wrote about "some of my very personal experiences, like breaking up with girlfriends and having bad relationships, feeling that death void that the person in the song is feeling. Very lonely, sick."[57] While Cobain regarded In Utero as "for the most part very impersonal",[58] its lyrics deal with his parents' divorce, his newfound fame and the public image and perception of himself and Courtney Love on "Serve the Servants", with his enamored relationship with Love conveyed through lyrical themes of pregnancy and the female anatomy on "Heart-Shaped Box."

Cobain was affected enough to write "Polly" from Nevermind after reading a newspaper story of an incident in 1987, when a 14-year-old girl was kidnapped after attending a punk rock show, then raped and tortured with a blowtorch. She escaped after gaining the trust of her captor Gerald Friend through flirting with him.[13]: 136 After seeing Nirvana perform, Bob Dylan cited "Polly" as the best of Nirvana's songs, and said of Cobain, "the kid has heart".[13]: 137 Patrick Süskind's novel Perfume: The Story of a Murderer inspired Cobain to write the song "Scentless Apprentice" from In Utero. The book is a historical horror novel about a perfumer's apprentice born with no body odor of his own but with a highly developed sense of smell, and who attempts to create the "ultimate perfume" by killing virginal women and taking their scent.[59]

Cobain immersed himself in artistic projects throughout his life, as much so as he did in songwriting. The sentiments of his artwork followed the same subjects of his lyrics, often expressed through a dark and macabre sense of humor. Noted were his fascination with physiology, his own rare medical conditions, and the human anatomy. According to Novoselic, "Kurt said that he never liked literal things. He liked cryptic things. He would cut out pictures of meat from grocery-store fliers, then paste these orchids on them ... And all this stuff on [In Utero] about the body—there was something about anatomy. He really liked that. You look at his art—there are these people, and they're all weird, like mutants. And dolls—creepy dolls."[60]

Cobain contributed backing guitar for a spoken word recording of beat poet William S. Burroughs' entitled The "Priest" They Called Him.[13]: 301 Cobain regarded Burroughs as a hero. During Nirvana's European tour Cobain kept a copy of Burroughs' Naked Lunch, purchased from a London bookstall.[13]: 189–190 Cobain met with Burroughs at his home in Lawrence, Kansas in October 1993. Burroughs expressed no surprise at Cobain's death: "It wasn't an act of will for Kurt to kill himself. As far as I was concerned, he was dead already."[61]

Equipment

In a Guitar World retrospective, Cobain's guitar tone was deemed "one of the most iconic" in the history of the electric guitar, while noting that rather than relying on expensive or vintage items, Cobain used "an eccentric cache of budget models, low-end imports and pawn shop prizes." Cobain stated in a 1992 interview, "Junk is always best," but denied this was a punk statement and claimed it was a necessity, as he had trouble finding high quality lefthanded guitars.[62]

Cobain's first guitar was a used electric guitar from Sears that he received on his 14th birthday. He took guitar lessons long enough to learn AC/DC's "Back in Black" and began playing with local kids. Cobain found the guitar smashed after leaving it in a locker, but he was able to purchase new equipment, including a Peavey amp, by recovering and selling his stepfather's gun collection, which his mother had dumped in a river after discovering his infidelity.[62] Upon forming what would be Nirvana, Cobain was playing a Fender Champ amplifier and a righthanded Univox Hi-Flier guitar he flipped over and strung for lefthanded playing.[62]

For the recording of Bleach, Cobain needed to borrow a Fender Twin Reverb due to his main amplifier, a solid-state Randall, being repaired at the time, but as the Twin Reverb's speakers were blown, he was forced to pair it with an external cabinet featuring two 12" speakers. He used a Boss DS-1 for distortion, while playing Hi-Flier guitars, which cost him $100 each. Nirvana embarked on their first American tour in 1989, at the start of which Cobain played an Epiphone ET270; however, he destroyed the guitar onstage during a show, a subsequent habit that forced label Sub Pop to have to call local pawn shops looking for replacement guitars.[62] Cobain's first acoustic guitar, a Stella 12-string, cost him $31.21. Cobain strung it with six (or sometimes five) strings, and while the guitar's tuners had to be held together with duct tape, it sounded good enough that the guitar was later used to record the Nevermind tracks "Polly" and "Something in the Way."[62]

Despite receiving a $287,000 advance upon signing with Geffen Records, Cobain retained a preference for inexpensive gear.[62] He became a fan of Japanese-made Fender guitars ahead of recording Nevermind, due to their slim necks and wide availability in lefthanded orientation. These included several Stratocasters fitted with humbucker pickups in the bridge positions, as well as a 1965 Jaguar with DiMarzio pickups and a 1969 Competition Mustang, the latter of which Cobain cited as his favorite, despite noting, "They're cheap and totally inefficient, and they sound like crap and are very small."[62] For the album, Cobain used a rackmount system featuring a Mesa/Boogie Studio preamp, a Crown power amp, and Marshall cabinets. He also used a Vox AC30 and a Fender Bassman. Producer Butch Vig preferred to avoid pedals, but allowed Cobain to use his Boss DS-1, which Cobain considered a key part of his sound, as well as an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff fuzz pedal and a Small Clone chorus, which can be heard on songs like "Smells Like Teen Spirit," "Come As You Are," and "Aneurysm."[62]

Cobain used his '69 Mustang, '65 Jaguar, a custom Jaguar/Mustang, and a Hi-Flier for the In Utero recording sessions. To tour behind the album, Cobain placed an order for 10 Mustangs split between Fiesta Red and Sonic Blue. As the Fender Custom Shop was new, the guitars were to be shipped out two at a time over a period of months. By the time of his death, Cobain had received six of the guitars. The remaining four, waiting to be shipped, were instead sold as regular stock at Japanese music stores without informing buyers the guitars had been made for Cobain.[63]

For Nirvana's Unplugged performance, Cobain played a righthanded 1959 Martin D-18E acoustic guitar modified for lefthanded playing. The guitar became the most expensive ever sold when it fetched over $6 million at auction in 2020.[64] Cobain's 1969 Competition Mustang, which he also played in the "Smells Like Teen Spirit" music video, sold at a 2022 auction to Jim Irsay, owner of the Indianapolis Colts, for $4.5 million, with an original estimate of $600,000.[65]

Personal life

Relationships and family

There are differing accounts of exactly when and how Kurt Cobain first met Courtney Love. In his 1993 authorized biography of Nirvana, Michael Azerrad cites a January 21, 1989, Dharma Bums gig in Portland where Nirvana played as support,[66] while the Charles R. Cross 2001 Cobain biography has Love and Cobain meeting at the same Satyricon nightclub venue in Portland but a different Nirvana show, January 12, 1990,[67][13]: 201 when both still led ardent underground rock bands.[68] Love made advances soon after they met, but Cobain was evasive. Early in their interactions, Cobain broke off dates and ignored Love's advances because he was unsure if he wanted a relationship. Cobain noted, "I was determined to be a bachelor for a few months [...] But I knew that I liked Courtney so much right away that it was a really hard struggle to stay away from her for so many months."[11]: 172–173 Everett True, who was an associate of both Cobain and Love, disputes those versions of events in his 2006 book, claiming that he himself introduced the couple on May 17, 1991.[69][70]

Cobain was already aware of Love through her role in the 1987 film Straight to Hell. According to True, the pair were formally introduced at an L7 and Butthole Surfers concert in Los Angeles in May 1991.[71] In the weeks that followed, after learning from Grohl that Cobain shared mutual interests with her, Love began pursuing Cobain. In late 1991, the two were often together and bonded through drug use.[11]: 172

On February 24, 1992, a few days after the conclusion of Nirvana's "Pacific Rim" tour, Cobain and Love were married on Waikiki Beach in Hawaii. Love wore a satin and lace dress once owned by Frances Farmer, and Cobain donned a Guatemalan purse and wore green pajamas, because he had been "too lazy to put on a tux." Eight people were in attendance at the ceremony, including Grohl, but not Novoselic.[72] Love said she was warned by the Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon that marrying Cobain would "destroy her life"; Love responded: "'Whatever! I love him, and I want to be with him!' ... It wasn't his fault. He wasn't trying to do that."[68]

The couple's daughter, Frances Bean Cobain, was born August 18, 1992.[73] A sonogram was included in the artwork for Nirvana's single, "Lithium."[74] In a 1992 Vanity Fair article, Love admitted to a drug binge with Cobain in the early weeks of her pregnancy.[75] At the time, she claimed that Vanity Fair had misquoted her. Love later admitted to using heroin before knowing she was pregnant.[73][76] The couple were asked by the press if Frances was addicted to drugs at birth.[11] The Los Angeles County Department of Children's Services visited the Cobains days after Love gave birth and later took them to court, stating that their drug usage made them unfit parents.[11][77][78]

Sexuality

In October 1992, when asked, "Well, are you gay?" by Monk Magazine, Cobain replied, "If I wasn't attracted to Courtney, I'd be a bisexual."[79] In another interview, he described identifying with the gay community in The Advocate, stating, "I'm definitely gay in spirit and I probably could be bisexual" and "if I wouldn't have found Courtney, I probably would have carried on with a bisexual life-style", but also that he was "more sexually attracted to women".[80][81] He described himself as being "feminine" in childhood, and often wore dresses and other stereotypically feminine clothing. Some of his song lyrics, as well as phrases he would use to vandalize vehicles and a bank, included "God is gay",[80] "Jesus is gay", "HOMOSEXUAL SEX RULES",[80] and "Everyone is gay". One of his personal journals states, "I am not gay, although I wish I were, just to piss off homophobes."[42]

Cobain advocated for LGBTQ+ rights, including traveling to Oregon to perform at a benefit opposing the 1992 Oregon Ballot Measure 9,[80] and supported local bands with LGBTQ+ members. He reported having felt "different" from the age of seven, and was a frequent target of homophobic bullying in his school due to his having a "gay friend".[82] Cobain was interviewed by two gay magazines, Out and The Advocate;[83] the 1993 interview with The Advocate being described as "the only [interview] the band's lead singer says he plans to do for Incesticide",[80] an album whose liner notes included a statement decrying homophobia, racism and misogyny:[80]

If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us—leave us the fuck alone! Don't come to our shows and don't buy our records.

Health and addiction

At school Cobain was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and was prescribed ritalin.[84] Throughout most of his life, Cobain had chronic bronchitis and intense physical pain due to an undiagnosed chronic stomach condition.[11]: 66 In an interview with Jon Savage in 1993 he said, "Every time I've had an endoscope, they find a red irritation in my stomach. But it's psychosomatic, It's all from anger. And screaming". He then goes onto mention that he, "had minor scoliosis in junior high".[85] According to The Telegraph, Cobain had depression.[86] In 1993, he told Michael Azerrad that he had narcolepsy and manic depression.[87] His cousin brought attention to the family history of suicide, mental illness and alcoholism, noting that two of her uncles had died by suicide with guns.[88]

According to Cross, Cobain suffered a mental breakdown midway through Nirvana's show in Rome on November 27, 1989. After smashing his guitar, he climbed a 30 ft speak stack and shouted, "I'm going to killing myself!".[89] Eventually he climbed down and took the following day off, sightseeing with Sub Pop manager, Bruce Pavitt.[90] Cobain completed the remaining five European tour dates and returned to the USA.

He first drank alcohol in 7th grade (c. 12 yrs)[91] and he often drank to excess throughout his life. His first drug experience was with cannabis in 1980, at age 13. He regularly used the drug during adulthood.[13]: 76 Cobain also had a period of consuming "notable" amounts of LSD, as observed by Marander,[13]: 75 and had been involved in solvent abuse as a teenager.[13] Novoselic said he was "really into getting fucked up: drugs, acid, any kind of drug".[13]: 76 He occasionally experimented with meth or cocaine when the band were on tour.[92] One example was when Novoselic and Cobain took cocaine after their gig in New York on July 18, 1989.[93] Cobain first took heroin in 1986, administered to him by a dealer in Tacoma, Washington, who had previously supplied him with oxycodone and aspirin.[11]: 41 Cobain used heroin sporadically for several years; by the end of 1991, his use had developed into addiction. Cobain claimed that he was "determined to get a habit" as a way to self-medicate his stomach condition. "It started with three days in a row of doing heroin and I don't have a stomach pain. That was such a relief," he said.[11]: 236 However, his longtime friend Buzz Osborne disputes this, saying that his stomach pain was more likely caused by his heroin use: "He made it up for sympathy and so he could use it as an excuse to stay loaded. Of course he was vomiting—that's what people on heroin do, they vomit. It's called 'vomiting with a smile on your face'."[94] Cobain told Novoselic in 1990 that he had used heroin and he spoke to Grohl about it in January 1991.[95]

Cobain's heroin use began to affect Nirvana's Nevermind tour. During a 1992 photoshoot with Michael Lavine, before their first Saturday Night Live performance on January 11, he fell asleep several times, having used heroin beforehand. Cobain told biographer Michael Azerrad: "They're not going to be able to tell me to stop. So I really didn't care. Obviously to them it was like practicing witchcraft or something. They didn't know anything about it so they thought that any second, I was going to die."[11]: 241

The morning after the band's performance on Saturday Night Live in 1992, Cobain experienced his first near-death overdose after injecting heroin; Love resuscitated him.[96]

On May 2, 1993 Cobain overdosed at his home in Seattle and Love called the paramedics. He was taken to Harboview Medical Center, but was discharged the same day.[97]

Prior to a performance at the New Music Seminar in New York City on July 23, 1993, Cobain suffered another overdose. Rather than calling for an ambulance, Love injected Cobain with naloxone to resuscitate him. Cobain proceeded to perform with Nirvana, giving the public no indication that anything had happened.[13]: 296–297

By March 1994, Love had "seen Kurt close to death from heroin overdoses on more than a dozen occasions," according to Cross.[98]

Death

Following a tour stop at Terminal Eins in Munich, Germany, on March 1, 1994, Cobain was diagnosed with bronchitis and severe laryngitis. He flew to Rome the next day for medical treatment, and was joined there by his wife, Courtney Love, on March 3. The next morning, Love awoke to find that Cobain had overdosed on a combination of champagne and Rohypnol. Cobain was rushed to the hospital and was unconscious for the rest of the day. Dave Grohl mentioned in his memoir[99] that he received a phone call at this time saying Cobain had died. However, a few minutes later he was called again and told that the singer was hospitalized but stable.[100] Love later said that the incident was Cobain's first suicide attempt.[101] After five days, Cobain was released and returned to Seattle.[10]

On March 18, 1994, Love phoned the Seattle police informing them that Cobain was suicidal and had locked himself in a room with a gun. Police arrived and confiscated several guns and a bottle of pills from Cobain, who insisted that he was not suicidal and had locked himself in the room to hide from Love.[102]

Love arranged an intervention regarding Cobain's drug use on March 25, 1994. The ten people involved included musician friends, record company executives, and one of Cobain's closest friends, Dylan Carlson. Cobain reacted with anger, insulting and heaping scorn on the participants, and locked himself in the upstairs bedroom. However, by the end of the day, Cobain agreed to undergo a detox program, and he entered a residential facility in Los Angeles for a few days on March 30, 1994.[103][104]

The following night, Cobain left the facility and flew to Seattle. On the flight, he sat near Duff McKagan of Guns N' Roses. Despite Cobain's animosity towards Guns N' Roses, Cobain "seemed happy" to see McKagan. McKagan later said that he knew from "all of my instincts that something was wrong".[13]: 331 Most of Cobain's friends and family were unaware of his whereabouts. On April 7, amid rumors of Nirvana breaking up, the band pulled out of the 1994 Lollapalooza festival.[105]

On April 8,[106] Cobain's body was discovered at his Lake Washington Boulevard home by an electrician,[107] who had arrived to install a security system. A suicide note was found, addressed to Cobain's childhood imaginary friend Boddah, that stated that Cobain had not "felt the excitement of listening to as well as creating music, along with really writing ... for too many years now". Cobain's body had been there for days; the coroner's report estimated he died on April 5, 1994, at the age of 27.[108]

Aftermath

A public vigil was held on April 10, at a park at Seattle Center, drawing approximately 7,000 mourners.[11]: 346 Prerecorded messages by Novoselic and Love were played at the memorial. Love read portions of the suicide note to the crowd, crying and chastising Cobain. Near the end of the vigil, Love distributed some of Cobain's clothing to those who remained.[11]: 350 Grohl said that the news of Cobain's death was "probably the worst thing that has happened to me in my life. I remember the day after that I woke up and I was heartbroken that he was gone. I just felt like, 'Okay, so I get to wake up today and have another day and he doesn't.'"[109][110][111]

Billboard, reporting from Seattle on April 23, stated that within a few hours of Cobain's death being confirmed on April 8, the only remaining Nirvana titles at Park Ave Records on Queen Anne Avenue were two "Heart-Shaped Box" import CD singles. A marketing director at the three-store Cellophane Square chain said that "all three stores sold about a few hundred CDs, singles, and vinyl by the morning of April 9". A buyer at Tower Records on Mercer Street said: "It's a pathetic scene, everything is going out the door. If people were really fans, they would've had this stuff already."[112] In the United Kingdom, sales of Nirvana releases rose dramatically immediately after Cobain's death.[113]

Grohl believed that he knew Cobain would die at an early age, saying that "sometimes you just can't save someone from themselves", and "in some ways, you kind of prepare yourself emotionally for that to be a reality".[114] Dave Reed, who for a short time had been Cobain's foster father, said that "he had the desperation, not the courage, to be himself. Once you do that, you can't go wrong, because you can't make any mistakes when people love you for being yourself. But for Kurt, it didn't matter that other people loved him; he simply didn't love himself enough."[13]: 351

A final ceremony was arranged by Cobain's mother on May 31, 1999, and was attended by Love and Tracy Marander. As a Buddhist monk chanted, daughter Frances Bean scattered Cobain's ashes into McLane Creek in Olympia, the city where he "had found his true artistic muse".[13]: 351 In 2006, Love said she retained Cobain's ashes, kept in a bank vault in Los Angeles because "no cemetery in Seattle will take them".[68]

Cobain's death became a topic of public fascination and debate.[115] His artistic endeavors and struggles with addiction, illness and depression, as well as the circumstances of his death, have become a frequent topic of controversy. According to a spokesperson for the Seattle Police Department, the department receives at least one weekly request to reopen the investigation, resulting in the maintenance of the basic incident report on file.[116]

In March 2014, the Seattle police developed four rolls of film that had been left in an evidence vault; no reason was provided for why the rolls were not developed earlier. According to the Seattle police, the 35mm film photographs show the scene of Cobain's dead body more clearly than previous Polaroid images taken by the police. Detective Mike Ciesynski, a cold case investigator, was instructed to look at the film because "it is 20 years later and it's a high media case". Ciesynski stated that Cobain's death remains a suicide and that the images would not have been released publicly.[116] The photos in question were later released, one by one, weeks before the 20th anniversary of Cobain's death. One photo shows Cobain's arm, still wearing the hospital bracelet from the drug rehab facility he had left just a few days prior to returning to Seattle. Another photo shows Cobain's foot resting next to a bag of shotgun shells, one of which was used in his death.[117]

Legacy

Cobain is remembered as one of the most influential rock musicians in the history of alternative music.[118] His angst-fueled songwriting[119] and anti-establishment persona[120] led him to be referenced as the spokesman of Generation X. In addition, Cobain's songs widened the themes[121] of mainstream rock music of the 1980s to discussion of personal reflection and social issues.[122] On April 10, 2014, Nirvana was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Grohl, Novoselic and Love accepted the accolade at the ceremony, where Cobain was also remembered.[123] Cobain is one of the best-known members of the 27 Club,[124] a list of musicians who died when they were 27 years old.

Music & Media reporting on April 23, 1994, after Cobain had died, stated that Jørgen Larsen, the president of MCA Music Entertainment International was asked where he thought Cobain stood in terms of his contribution to contemporary music, and Larsen replied that "If anybody comes out of nowhere to sell 11 or 12 million albums you have to conclude that there's something there. He wasn't just a one-hit wonder."[125]

According to music journalist Paul Lester, who worked at Melody Maker at the time, Cobain's suicide triggered an immediate reappraisal of his work. He wrote: "The general impression offered by In Utero was that Cobain was some kind of whiny, self-absorbed, grunge, misery guts who could make routinely powerful music but was hardly a suffering godhead. You could almost hear a collective sigh of relief after April 5, 1994, that Cobain could no longer further sully his reputation; that the myth-making machinery could finally be cranked into action."[126]

Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins referred to Cobain as "the Michael Jordan of our generation",[127] and said that Cobain opened the door for everyone in the 1990s alternative rock scene.[128] Lars Ulrich of Metallica reflected on Cobain's influence stating that "with Kurt Cobain you felt you were connecting to the real person, not to a perception of who he was—you were not connecting to an image or a manufactured cut-out. You felt that between you and him there was nothing—it was heart-to-heart. There are very few people who have that ability."[129] In 1996, the Church of Kurt Cobain was established in Portland, Oregon,[130][131] but it was later claimed by some media outlets to have been a media hoax.[132][133] Reflecting on Cobain's death over 10 years later, MSNBC's Eric Olsen wrote, "In the intervening decade, Cobain, a small, frail but handsome man in life, has become an abstract Generation X icon, viewed by many as the 'last real rock star' ... a messiah and martyr whose every utterance has been plundered and parsed."[134]

In 2003, David Fricke of Rolling Stone ranked Cobain the 12th greatest guitarist of all time.[135] He was later ranked the 73rd greatest guitarist and 45th greatest singer of all time by the same magazine,[136][8] and by MTV as seventh in the "22 Greatest Voices in Music".[137] In 2006, he was placed at number twenty by Hit Parader on their list of the "100 Greatest Metal Singers of All Time".[138]

In 2005, a sign was put up in Aberdeen, Washington, that read "Welcome to Aberdeen—Come As You Are" as a tribute to Cobain. The sign was paid for and created by the Kurt Cobain Memorial Committee, a non-profit organization created in May 2004 to honor Cobain. The Committee planned to create a Kurt Cobain Memorial Park and a youth center in Aberdeen. Because Cobain was cremated and his remains scattered into the Wishkah River in Washington, many Nirvana fans visit Viretta Park, near Cobain's former Lake Washington home to pay tribute. On the anniversary of his death, fans gather in the park to celebrate his life and memory.[139] Controversy erupted in July 2009 when a monument to Cobain in Aberdeen along the Wishkah River included the quote "... Drugs are bad for you. They will fuck you up." The city ultimately decided to sandblast the monument to replace the expletive with "f---",[140] but fans immediately drew the letters back in.[141] In December 2013, the small city of Hoquiam, where Cobain once lived, announced that April 10 would become the annual Nirvana Day.[142] Similarly, in January 2014, Cobain's birthday, February 20, was declared annual "Kurt Cobain Day" in Aberdeen.[142]

In June 2020, the 1959 Martin D-18E acoustic-electric guitar used by Cobain for Nirvana's MTV Unplugged performance sold at auction for $6,010,000 to Peter Freedman the chairman of Røde Microphones. It was the most expensive guitar and the most expensive piece of band memorabilia ever sold.[143] In May 2022, Cobain's Lake Placid Blue Fender Mustang guitar sold at auction for $4.5 million to Jim Irsay, making it the second-most valuable guitar ever sold and the most valuable electric guitar.[144]

In July 2021, the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation confirmed that Cobain's childhood home in Aberdeen would be included on their Heritage Register, and that the owner would be making it into an exhibit for people to visit.[145][146]

Media

Books

Prior to Cobain's death, Michael Azerrad published Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana, a book chronicling Nirvana's career from its beginning, as well as the personal histories of the band members. The book explored Cobain's drug addiction, as well as the countless controversies surrounding the band. After Cobain's death, Azerrad republished the book to include a final chapter discussing the last year of Cobain's life. The book involved the band members themselves, who provided interviews and personal information to Azerrad specifically for the book. In 2006, Azerrad's taped conversations with Cobain were transformed into a documentary about Cobain, titled Kurt Cobain: About a Son. Though this film does not feature any music by Nirvana, it has songs by the artists that inspired Cobain.

Journalists Ian Halperin and Max Wallace published their investigation of any possible conspiracy surrounding Cobain's death in their 1998 book Who Killed Kurt Cobain?. Halperin and Wallace argued that, while there was not enough evidence to prove a conspiracy, there was more than enough to demand that the case be reopened.[147] The book included the journalists' discussions with Tom Grant, who had taped nearly every conversation that he had undertaken while he was in Love's employ. Over the next several years, Halperin and Wallace collaborated with Grant to write a second book, 2004's Love and Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain.

In 2001, writer Charles R. Cross published a biography of Cobain, titled Heavier Than Heaven. For the book, Cross conducted over 400 interviews, and was given access by Courtney Love to Cobain's journals, lyrics, and diaries.[148] Cross' biography was met with criticism, including allegations of Cross accepting secondhand (and incorrect) information as fact.[149] Friend Everett True—who derided the book as being inaccurate, omissive, and highly biased—said Heavier than Heaven was "the Courtney-sanctioned version of history"[150] or, alternatively, Cross's "Oh, I think I need to find the new Bruce Springsteen now" Kurt Cobain book.[151] However, beyond the criticism, the book contained details about Cobain and Nirvana's career that would have otherwise been unnoted. In 2008, Cross published Cobain Unseen, a compilation of annotated photographs and creations and writings by Cobain throughout his life and career.[152]

In 2002, a sampling of Cobain's writings was published as Journals. The book fills 280 pages with a simple black cover; the pages are arranged somewhat chronologically (although Cobain generally did not date them). The journal pages are reproduced in color, and there is a section added at the back with explanations and transcripts of some of the less legible pages. The writings begin in the late 1980s and were continued until his death. A paperback version of the book, released in 2003, included a handful of writings that were not offered in the initial release. In the journals, Cobain talked about the ups and downs of life on the road, made lists of what music he was enjoying, and often scribbled down lyric ideas for future reference. Upon its release, reviewers and fans were conflicted about the collection. Many were elated to be able to learn more about Cobain and read his inner thoughts in his own words, but were disturbed by what was viewed as an invasion of his privacy.[153]

In 2019, on the 25th anniversary of Cobain's death, former Nirvana manager, Danny Goldberg, published Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain. In promotion of the book, Goldberg stated:

I think that in terms of icons, Kurt was kind of the last icon of the rock era and then the hip-hop era started.

Then, obviously, in our kid's generation, hip-hop has been a dominant voice for adolescence. It's not the only one, there were still rock artists but not only was he iconic in terms of depth in which he touched people, that music was pop. Those songs were as big as Rihanna, Travis Scott or Justin Bieber or anything today.

They were pop hits as well as touching the underground culture. That fusion of pop and underground, I don't think rock has produced someone else who could do that since Kurt. I think he's arguably the last of that era.

You could almost have bookends of an era that started with The Beatles and ended with Kurt. I mean, yeah, there was rock and roll before The Beatles but The Beatles broadened it and I think you can make that argument.[154][155][156]

Film and television

In the 1998 documentary Kurt & Courtney, filmmaker Nick Broomfield investigated Tom Grant's claim that Cobain was actually murdered. He took a film crew to visit a number of people associated with Cobain and Love; Love's father, Cobain's aunt, and one of the couple's former nannies. Broomfield also spoke to Mentors bandleader Eldon "El Duce" Hoke, who claimed Love offered him $50,000 to kill Cobain. Although Hoke claimed he knew who killed Cobain, he failed to mention a name, and offered no evidence to support his assertion. Broomfield inadvertently captured Hoke's last interview, as he died days later, reportedly hit by a train. However, Broomfield felt he had not uncovered enough evidence to conclude the existence of a conspiracy. In a 1998 interview, Broomfield summed it up by saying:

I think that he committed suicide. I don't think there's a smoking gun. And I think there's only one way you can explain a lot of things around his death. Not that he was murdered, but that there was just a lack of caring for him. I just think that Courtney had moved on, and he was expendable.[157]

Broomfield's documentary was noted by The New York Times to be a rambling, largely speculative and circumstantial work, relying on flimsy evidence as was his later documentary Biggie & Tupac.[158]

The documentary Teen Spirit: The Tribute to Kurt Cobain was released as a home video in 1996,[159] and on DVD in 2001.[160] The Vigil is a 1998 comedy film about a group of young people who travel from Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada to Seattle in the United States to attend the memorial vigil for Cobain in 1994. It stars Donny Lucas and Trevor White.[161][162]

Gus Van Sant loosely based his 2005 movie Last Days on the events in the final days of Cobain's life, starring Michael Pitt as the main character Blake who was based on Cobain.[163]

In 2006, the Jon Brewer directed documentary, All Apologies: Kurt Cobain 10 Years On,[164][165] and the BBC documentary, The Last 48 Hours of Kurt Cobain, were released.[166][167] In January 2007, Love began to shop the biography Heavier Than Heaven to various movie studios in Hollywood to turn the book into an A-list feature film about Cobain and Nirvana.[168]

A Brett Morgen film, entitled Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2015, followed by small-screen and cinema releases.[169] Morgen said that documentary "will be this generation's The Wall".[170]

Soaked in Bleach is a 2015 American docudrama directed by Benjamin Statler. The film details the events leading up to the death of Kurt Cobain, as seen through the perspective of Tom Grant, the private detective who was hired by Courtney Love to find Cobain, her husband, shortly before his death in 1994. It also explores the premise that Cobain's death was not a suicide. The film stars Tyler Bryan as Cobain and Daniel Roebuck as Grant, with Sarah Scott portraying Courtney Love and August Emerson as Dylan Carlson.[171] Love's legal team issued a cease-and-desist letter against theaters showing the documentary.[172]

Regarding the depiction of Nirvana, and in particular Kurt Cobain, the indie rock author Andrew Earles wrote:

Never has a rock band's past been so retroactively distorted into an irreversible fiction by incessant mythologizing, conjecture, wild speculation, and romanticizing rhetoric. The Cobain biographical narrative – specifically in regard to the culturally irresponsible mishandling of subjects such as drug abuse, depression, and suicide – is now impenetrable with inaccurate and overcooked connectivity between that which is completely unrelated, too chronologically disparate, or just plain untrue.

— Andrew Earles[173]

Matt Reeves' film The Batman depicts a version of Bruce Wayne, performed by Robert Pattinson, that was loosely inspired by Cobain. Reeves stated, "when I write, I listen to music, and as I was writing the first act, I put on Nirvana's 'Something in the Way,' that's when it came to me that, rather than make Bruce Wayne the playboy version we've seen before, there's another version who had gone through a great tragedy and become a recluse. So I started making this connection to Gus Van Sant's Last Days, and the idea of this fictionalised version of Kurt Cobain being in this kind of decaying manor."[174] "Something in the Way" was used in trailers to promote The Batman prior to its release and is featured twice in the film.[175][176]

To mark the 30th anniversary of Cobain's death a new documentary titled Kurt Cobain: Moments That Shook Music aired on BBC Two and BBC iPlayer on April 13, 2024.[177][178][179]

Theatre

In September 2009, the Roy Smiles play Kurt and Sid debuted at the Trafalgar Studios in London's West End. The play, set in Cobain's greenhouse on the day of his suicide, revolves around the ghost of Sid Vicious visiting Cobain to try to convince him not to kill himself. Cobain was played by Shaun Evans.[180]

Video games

Cobain was included as a playable character in the 2009 video game Guitar Hero 5; he can be used to play songs by Nirvana and other acts. Novoselic and Grohl released a statement condemning the inclusion and urging the developer, Activision, to alter it, saying they had no control over the use of Cobain's likeness. Love denied that she had given permission, saying it was "the result of a cabal of a few assholes' greed", and threatened to sue. The vice-president of Activision said that Love had contributed photos and videos to the development and had been "great to work with".[181]

Discography

Nirvana

For a complete list of all Nirvana releases, see Nirvana discography.

Posthumous albums

| Title | Album details | Chart positions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [182] |

BE (Ultratop Flanders) [183] |

BE (Ultratop Wallonia) [184] |

ES [185] |

FR [186] |

ITL [187] |

NL [188] |

SWI [189] |

UK [190] | ||

| Montage of Heck: The Home Recordings |

|

121 | 42 | 78 | 94 | 65 | 47 | 51 | 47 | 51 |

Posthumous singles

| Song | Year | Peak chart positions | Album | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US (physical sales) [191] |

UK (physical sales) [192] | |||

| "And I Love Her"/"Sappy" | 2015 | 2 | 2 | Montage of Heck: The Home Recordings |

Posthumous videos

- Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck (DVD and Blu-ray) (2015)

Collaborations

| Release | Artist | Year | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Where Did You Sleep Last Night?" | The Jury | 1989 | In 1989, members of Nirvana and fellow band Screaming Trees formed a side project known as the Jury (a Lead Belly cover band).[35]

"Where Did You Sleep Last Night?" was later released on Mark Lanegan's album, The Winding Sheet, in 1990.[193] "Grey Goose", "Ain't It a Shame" and "They Hung Him on a Cross" were later released on Nirvana's B-sides collection, With the Lights Out, in 2004.[193] |

| "Grey Goose" | |||

| "Ain't It a Shame" | |||

| "They Hung Him on a Cross" | |||

| "Scratch It Out" / "Bikini Twilight" | The Go Team | 1989 | |

| The Winding Sheet | Mark Lanegan | 1990 | Background vocals on "Down in the Dark" and guitar on "Where Did You Sleep Last Night". |

| Earth's demo | Earth | Lead vocals for song "Divine Bright Extraction"[194] and backing vocals for "A Bureaucratic Desire For Revenge".[195] Lead vocals for a cover song "Private Affair" (original by The Saints), but that was never released.[196] | |

| The "Priest" They Called Him | William S. Burroughs and Kurt Cobain | 1993 | Background guitar noise. |

| Houdini | Melvins | Co-producer, Guitar on "Sky Pup" and percussion on "Spread Eagle Beagle". |

References

- ^ Shoup, Brad (March 24, 2022). "'I Will Crawl Away For Good': 20 Years Ago, Nirvana Reconquered Modern Rock With an Uncanny Old New Song". Billboard. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (June 20, 2019). "Nirvana's 20 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (April 5, 2019). "From the Archives: Nirvana's Kurt Cobain was a reluctant hero who spoke to his generation". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Mazullo, Mark (2000). "The Man Whom the World Sold: Kurt Cobain, Rock's Progressive Aesthetic, and the Challenges of Authenticity". The Musical Quarterly. 84 (4). Oxford University Press: 713–749. doi:10.1093/mq/84.4.713. ISSN 0027-4631. JSTOR 742606.

- ^ Hirschberg, Lynn. "Strange Love: The Story of Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love". HWD. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "The27s.com roster". January 20, 2018. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018.

- ^ "Kurt Cobain's Downward Spiral and Last Days". Rolling Stone. June 2, 1994. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "100 Greatest Singers of All Time: 45) Kurt Cobain". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Cross, Charles (2008). Cobain Unseen. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03372-5.

- ^ a b c Halperin, Ian; Wallace, Max (1998). Who Killed Kurt Cobain?. New York City: Birch Lane Press. ISBN 1-55972-446-3. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Azerrad, Michael (1993). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. New York City: Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47199-8.

- ^ a b Addams Reitwiesner, William. "Ancestry of Frances Bean Cobain". Wargs.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as Cross, Charles R. (2001). Heavier Than Heaven. New York City: Hyperion Books. ISBN 0-7868-6505-9.

- ^ Fox, Aine (March 24, 2010). "Nirvana legend Kurt Cobain's roots traced to Co Tyrone". Belfast Telegraph. Belfast, northern Ireland: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Savage, Jon (August 15, 1993). "Sounds Dirty: The Truth About Nirvana. By Jon Savage: Articles, reviews and interviews from Rock's Backpages". Rocksbackpages.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Audrey Davies. "The Visual Art of 8 More Famous Musicians – Part 2". Rock Cellar Magazine. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ "In Which We Discard A Heart-Shaped Box". Archived from the original on August 23, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ Savage, John. "Kurt Cobain: The Lost Interview". NirvanaFreak.net. Archived from the original on April 30, 2004. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Live Nirvana | Interview Archive | 1992 | April ??, 1992 - Los Angeles, CA, US". www.livenirvana.com.

- ^ a b c d e Gillian G. Gaar. Entertain Us!: The Rise of Nirvana Penguin, 2012

- ^ Hankey, Rick (December 13, 1993). Kurt Cobain: "These kids really like our band". Seattle, WA: MTV.

Question: So it was your friend, the Melvins' Buzz Osborne, who introduced you to punk rock?

Cobain: Yeah, ... I was living in Aberdeen, and I was going to school in Montesano, which is about 30 miles away. I had him in an art class and electronics class and I remember just hanging out with him. He had a few punk rock magazines, and I would look at them and just like... "Oh." I was just mesmerized. ... - ^ Arnold, Gina (January–February 1992). "Better Dead Than Cool". Option.

Kurt Cobain: [The Melvins] started playing punk rock and had a free concert right behind Thriftways supermarket where Buzz worked, and they plugged into the city power supply and played punk rock music for about 50 redneck kids. When I saw them play, it just blew me away. I was instantly a punk rocker. I abandoned all my friends, 'cause they didn't like any of the music. Then I asked Buzz to make me that compilation tape of punk rock songs and got a spike haircut. ...

- ^ Cross, Charles R. "Requiem for a Dream." Guitar World. October 2001.

- ^ Michael Azerrad. Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday, 1993. ISBN 0-385-47199-8.

- ^ Gillian G. Gaar. The Rough Guide to Nirvana. Penguin, 1993.

- ^ "Top-Selling Artists". Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ^ "Nirvana catalogue to be released on vinyl". CBC.ca. March 21, 2009. Archived from the original on June 26, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Michael Azerrad (April 16, 1992). "Nirvana: Inside the Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (April 5, 2014). "Kurt Cobain: an icon of alienation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c Kowalewski, Al; Nunez, Cake (March 1992). "An Interview with... Kurt Cobain". Flipside. No. 78. Los Angeles, California (published May–June 1992). p. 37. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Gaar, Gillian G. (2006). In Utero. United States: Continuum Publishing. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0-8264-1776-0.

- ^ Barrett, Dawson (January 6, 2014). "King of the Outcast Teens: Kurt Cobain and the Politics of Nirvana". Portside. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ Villarreal, David (December 7, 2017). "In 1992, Nirvana Fought an Anti-Gay Ballot Initiative (and Wanted to Burn Down GOP Headquarters)". Hornet. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ Gold, Jonathan (September 29, 1992). "POP MUSIC REVIEW: Bands Get Together for Rock for Choice". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "Live Nirvana | LiveNirvana.com Sessions History | Studio Sessions | (The Jury) August 20 & 28, 1989 – Reciprocal Recording, Seattle, WA, US". LiveNIRVANA. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ True, Everett (2006). Nirvana – The True Story. Omnibus Press. pp. 146, 636. ISBN 978-1-84449-640-2.

- ^ True, Everett (March 13, 2007). Nirvana: The Biography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0306815546.

- ^ "LIVE NIRVANA SESSIONS HISTORY: (Bathtub Is Real) 1990 – ?, Olympia, WA, US". livenirvana.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "When Kurt Cobain met William Burroughs". DangerousMinds. October 26, 2012. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ a b "The "Priest" They Called Him: A Dark Collaboration Between Kurt Cobain & William S. Burroughs". Open Culture. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ Savage, John. "Kurt Cobain: The Lost Interview". NirvanaFreak.net. Archived from the original on April 30, 2004. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d Cobain, Kurt (2002). Journals. New York City: Riverhead Hardcover. ISBN 978-1-57322-232-7.

- ^ Weller, Amy (September 5, 2013). "If it wasn't for Freddie Mercury... 13 artists inspired by the Queen icon". Gigwise. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Guarino, Mark (October 12, 2001). "Heavy heaven New Cobain bio sheds light on fallen hero". Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, Illinois). Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

Soon band member Roger "Buzz" Osborne started Cobain's schooling, loaning him records and old copies of the '70s rock magazine Creem.

- ^ Sorge, Claudio [in Italian] (March 1992). "Kurt Cobain, Il Punk Da Un Milione Di Dollari". Rumore (in Italian). Mezzago, Italy.

Kurt Cobain: Ci aggregammo subito ai Melvins, che erano anche loro di Aberdeen. Definitivamente sono il gruppo che ci ha maggiormente influenzato. Andavamo alle loro prove, ai loro concerti. Abbiamo suonato con loro in vari show. Abbiamo imparato quasi tutto da loro.

- ^ Michalski, Thomas (May 2, 2012). "The Melvins @ Turner Hall Ballroom". Shepherd Express. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Coiteux, Marc (September 21, 1991). "Interview September 21, 1991". LiveNirvana. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Carlos Miguel, Antonio (January 20, 1993). "Interview January 20, 1993". LiveNirvana. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Cobain, Kurt. "Kurt Cobain of Nirvana Talks About the Records That Changed His Life. Melody Maker. August 29, 1992.

- ^ a b c Fricke, David. "Kurt Cobain: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. January 27, 1994

- ^ Payne, Chris (November 18, 2014). "Nirvana's 'MTV Unplugged' 20 Years Later: Meat Puppets' Curt Kirkwood Looks Back". Billboard. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Laurence Romance (April 21, 2010). "Kurt Cobain interview Date: 08/10/1993 Location: Seattle Ze Full Version Uncut !!!". Romance Is Dead. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Stephen. "MTV Unplugged in New York – Nirvana". AllMusic. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ "Everybody Hurts Sometime". Newsweek. September 26, 1994. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Classic Albums—Nirvana: Nevermind (DVD). Isis Productions. 2004.

Kurt used to say that music comes first and lyrics comes second, and I think Kurt's main focus was melody

- ^ Sliver: The Best of the Box album booklet.

- ^ Morris, Chris. "The Year's Hottest Band Can't Stand Still". Musician, January 1992.

- ^ Savage, Jon. "Sounds Dirty: The Truth About Nirvana". The Observer. August 15, 1993.

- ^ Gaar 2006, pp. 42–43

- ^ "Krist Novoselic on Kurt Cobain's Writing Process". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Miles, Barry (2015). William S. Burroughs: A Life. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 621. ISBN 978-1-7802-2120-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gill, Chris (February 17, 2021). "The definitive Kurt Cobain gear guide: a deep dive into the Nirvana frontman's pawn shop prizes, turbo-charged stompboxes and blown woofers". guitarworld.com. Guitar World. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Stuart (May 21, 2022). "The story of Kurt Cobain's Fender Mustang guitars in Nirvana". musicradar.com. Music Radar. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (June 20, 2020). "Kurt Cobain's 'MTV Unplugged' Guitar Sells for $6 Million at Auction". rollingstone.com. Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ "Kurt Cobain's 'Smells Like Teen Spirit' guitar sells for $4.5 million at auction". nbcnews.com. NBC News. May 23, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (January 23, 2013). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Crown. ISBN 9780307833730.

- ^ Cross, Charles R. (March 13, 2012). Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain. Hachette Books. ISBN 9781401304515.

- ^ a b c Barton, Laura (December 11, 2006). "Love me do". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ True, Everett (November 4, 2009). Nirvana: The True Story. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857120137.

- ^ Nirvana - Uncensored on the Record. Coda Books. ISBN 9781781580059.

- ^ Everett True. "Wednesday 1 March". Archived from the original on February 6, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2012. Plan B Magazine Blogs. March 1, 2006.