Potassium nitrate

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Potassium nitrate

| |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.926 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E252 (preservatives) | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1486 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| KNO3 | |||

| Molar mass | 101.1032 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | white solid | ||

| Odor | odorless | ||

| Density | 2.109 g/cm3 (16 °C) | ||

| Melting point | 334 °C (633 °F; 607 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 400 °C (752 °F; 673 K) (decomposes) | ||

| |||

| Solubility | slightly soluble in ethanol soluble in glycerol, ammonia | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 15.3[3] | ||

| −33.7·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.335, 1.5056, 1.5604 | ||

| Structure | |||

| Orthorhombic, Aragonite | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

95.06 J/mol K | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−494.00 kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Oxidant, harmful if swallowed, inhaled, or absorbed on skin. Causes irritation to skin and eye area. | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| H272, H315, H319, H335 | |||

| P102, P210, P220, P221, P280 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | non-flammable (oxidizer) | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

1901 mg/kg (oral, rabbit) 3750 mg/kg (oral, rat)[4] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0184 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other anions

|

Potassium nitrite | ||

Other cations

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Potassium nitrate (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

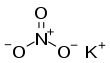

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with a sharp, salty, bitter taste and the chemical formula KNO3. It is a potassium salt of nitric acid. This salt consists of potassium cations K+ and nitrate anions NO−3, and is therefore an alkali metal nitrate. It occurs in nature as a mineral, niter (or nitre outside the US).[5] It is a source of nitrogen, and nitrogen was named after niter. Potassium nitrate is one of several nitrogen-containing compounds collectively referred to as saltpetre (or saltpeter in the US).[5]

Major uses of potassium nitrate are in fertilizers, tree stump removal, rocket propellants and fireworks. It is one of the major constituents of gunpowder (black powder).[6] In processed meats, potassium nitrate reacts with hemoglobin and myoglobin generating a red color.[7]

Etymology

[edit]Nitre, or potassium nitrate, because of its early and global use and production, has many names.

As for nitrate, Hebrew and Egyptian words for it had the consonants n-t-r, indicating likely cognation in the Greek nitron, which was Latinised to nitrum or nitrium. Thence Old French had niter and Middle English nitre. By the 15th century, Europeans referred to it as saltpetre,[8] specifically Indian saltpetre (Chilean saltpetre is sodium nitrate[9]) and later as nitrate of potash, as the chemistry of the compound was more fully understood.

The Arabs called it "Chinese snow" (Arabic: ثلج الصين, romanized: thalj al-ṣīn) as well as bārūd (بارود), a term of uncertain origin that later came to mean gunpowder. It was called "Chinese salt" by the Iranians/Persians[10][11][12] or "salt from Chinese salt marshes" (Persian: نمک شوره چينی namak shūra chīnī).[13]: 335 [14] The Tiangong Kaiwu, published in the 17th century by members of the Qing dynasty, detailed the production of gunpowder and other useful products from nature.

Historical production

[edit]From mineral sources

[edit]In Mauryan India saltpeter manufacturers formed the Nuniya & Labana caste.[15] Saltpeter finds mention in Kautilya's Arthashastra (compiled 300BC – 300AD), which mentions using its poisonous smoke as a weapon of war,[16] although its use for propulsion did not appear until medieval times.

A purification process for potassium nitrate was outlined in 1270 by the chemist and engineer Hasan al-Rammah of Syria in his book al-Furusiyya wa al-Manasib al-Harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices). In this book, al-Rammah describes first the purification of barud (crude saltpeter mineral) by boiling it with minimal water and using only the hot solution, then the use of potassium carbonate (in the form of wood ashes) to remove calcium and magnesium by precipitation of their carbonates from this solution, leaving a solution of purified potassium nitrate, which could then be dried.[17] This was used for the manufacture of gunpowder and explosive devices. The terminology used by al-Rammah indicated the gunpowder he wrote about originated in China.[18]

At least as far back as 1845, nitratite deposits were exploited in Chile and California.

From caves

[edit]Major natural sources of potassium nitrate were the deposits crystallizing from cave walls and the accumulations of bat guano in caves.[19] Extraction is accomplished by immersing the guano in water for a day, filtering, and harvesting the crystals in the filtered water. Traditionally, guano was the source used in Laos for the manufacture of gunpowder for Bang Fai rockets.[20]

Calcium nitrate, or lime saltpetre, was discovered on the walls of stables, from the urine of barnyard animals.[9]

Nitraries

[edit]Potassium nitrate was produced in a nitrary or "saltpetre works".[21] The process involved burial of excrements (human or animal) in a field beside the nitraries, watering them and waiting until leaching allowed saltpeter to migrate to the surface by efflorescence. Operators then gathered the resulting powder and transported it to be concentrated by ebullition in the boiler plant.[22][23]

Besides "Montepellusanus", during the thirteenth century (and beyond) the only supply of saltpeter across Christian Europe (according to "De Alchimia" in 3 manuscripts of Michael Scot, 1180–1236) was "found in Spain in Aragon in a certain mountain near the sea".[13]: 89, 311 [24]

In 1561, Elizabeth I, Queen of England and Ireland, who was at war with Philip II of Spain, became unable to import saltpeter (of which the Kingdom of England had no home production), and had to pay "300 pounds gold" to the German captain Gerrard Honrik for the manual "Instructions for making saltpeter to growe" (the secret of the "Feuerwerkbuch" -the nitraries-).[25]

Nitre bed

[edit]A nitre bed is a similar process used to produce nitrate from excrement. Unlike the leaching-based process of the nitrary, however, one mixes the excrements with soil and waits for soil microbes to convert amino-nitrogen into nitrates by nitrification. The nitrates are extracted from soil with water and then purified into saltpeter by adding wood ash. The process was discovered in the early 15th century and was very widely used until the Chilean mineral deposits were found.[26]

The Confederate side of the American Civil War had a significant shortage of saltpeter. As a result, the Nitre and Mining Bureau was set up to encourage local production, including by nitre beds and by providing excrement to government nitraries. On November 13, 1862, the government advertised in the Charleston Daily Courier for 20 or 30 "able bodied Negro men" to work in the new nitre beds at Ashley Ferry, S.C. The nitre beds were large rectangles of rotted manure and straw, moistened weekly with urine, "dung water", and liquid from privies, cesspools and drains, and turned over regularly. The National Archives published payroll records that account for more than 29,000 people compelled to such labor in the state of Virginia. The South was so desperate for saltpeter for gunpowder that one Alabama official reportedly placed a newspaper ad asking that the contents of chamber pots be saved for collection. In South Carolina, in April 1864, the Confederate government forced 31 enslaved people to work at the Ashley Ferry Nitre Works, outside Charleston.[27]

Perhaps the most exhaustive discussion of the niter-bed production is the 1862 LeConte text.[28] He was writing with the express purpose of increasing production in the Confederate States to support their needs during the American Civil War. Since he was calling for the assistance of rural farming communities, the descriptions and instructions are both simple and explicit. He details the "French Method", along with several variations, as well as a "Swiss method". N.B. Many references have been made to a method using only straw and urine, but there is no such method in this work.

French method

[edit]Turgot and Lavoisier created the Régie des Poudres et Salpêtres a few years before the French Revolution. Niter-beds were prepared by mixing manure with either mortar or wood ashes, common earth and organic materials such as straw to give porosity to a compost pile typically 4 feet (1.2 m) high, 6 feet (1.8 m) wide, and 15 feet (4.6 m) long.[28] The heap was usually under a cover from the rain, kept moist with urine, turned often to accelerate the decomposition, then finally leached with water after approximately one year, to remove the soluble calcium nitrate which was then converted to potassium nitrate by filtering through potash.

Swiss method

[edit]Joseph LeConte describes a process using only urine and not dung, referring to it as the Swiss method. Urine is collected directly, in a sandpit under a stable. The sand itself is dug out and leached for nitrates which are then converted to potassium nitrate using potash, as above.[29]

From nitric acid

[edit]From 1903 until the World War I era, potassium nitrate for black powder and fertilizer was produced on an industrial scale from nitric acid produced using the Birkeland–Eyde process, which used an electric arc to oxidize nitrogen from the air. During World War I the newly industrialized Haber process (1913) was combined with the Ostwald process after 1915, allowing Germany to produce nitric acid for the war after being cut off from its supplies of mineral sodium nitrates from Chile (see nitratite).

Modern production

[edit]Potassium nitrate can be made by combining ammonium nitrate and potassium hydroxide.

- NH4NO3 + KOH → NH3 + KNO3 + H2O

An alternative way of producing potassium nitrate without a by-product of ammonia is to combine ammonium nitrate, found in instant ice packs,[30] and potassium chloride, easily obtained as a sodium-free salt substitute.

- NH4NO3 + KCl → NH4Cl + KNO3

Potassium nitrate can also be produced by neutralizing nitric acid with potassium hydroxide. This reaction is highly exothermic.

- KOH + HNO3 → KNO3 + H2O

On industrial scale it is prepared by the double displacement reaction between sodium nitrate and potassium chloride.

- NaNO3 + KCl → NaCl + KNO3

Properties

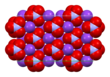

[edit]Potassium nitrate has an orthorhombic crystal structure at room temperature,[31] which transforms to a trigonal system at 128 °C (262 °F). On cooling from 200 °C (392 °F), another trigonal phase forms between 124 °C (255 °F) and 100 °C (212 °F).[32][33]

Sodium nitrate is isomorphous with calcite, the most stable form of calcium carbonate, whereas room-temperature potassium nitrate is isomorphous with aragonite, a slightly less stable polymorph of calcium carbonate. The difference is attributed to the similarity in size between nitrate (NO−3) and carbonate (CO2−3) ions and the fact that the potassium ion (K+) is larger than sodium (Na+) and calcium (Ca2+) ions.[34]

In the room-temperature structure of potassium nitrate, each potassium ion is surrounded by 6 nitrate ions. In turn, each nitrate ion is surrounded by 6 potassium ions.[31]

| Unit cell | Potassium coordination | Nitrate coordination |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Potassium nitrate is moderately soluble in water, but its solubility increases with temperature. The aqueous solution is almost neutral, exhibiting pH 6.2 at 14 °C (57 °F) for a 10% solution of commercial powder. It is not very hygroscopic, absorbing about 0.03% water in 80% relative humidity over 50 days. It is insoluble in alcohol and is not poisonous; it can react explosively with reducing agents, but it is not explosive on its own.[2]

Thermal decomposition

[edit]Between 550–790 °C (1,022–1,454 °F), potassium nitrate reaches a temperature-dependent equilibrium with potassium nitrite:[35]

- 2 KNO3 ⇌ 2 KNO2 + O2

Uses

[edit]Potassium nitrate has a wide variety of uses, largely as a source of nitrate.

Nitric acid production

[edit]Historically, nitric acid was produced by combining sulfuric acid with nitrates such as saltpeter. In modern times this is reversed: nitrates are produced from nitric acid produced via the Ostwald process.

Oxidizer

[edit]The most famous use of potassium nitrate is probably as the oxidizer in blackpowder. From the most ancient times until the late 1880s, blackpowder provided the explosive power for all the world's firearms. After that time, small arms and large artillery increasingly began to depend on cordite, a smokeless powder. Blackpowder remains in use today in black powder rocket motors, but also in combination with other fuels like sugars in "rocket candy" (a popular amateur rocket propellant). It is also used in fireworks such as smoke bombs.[36] It is also added to cigarettes to maintain an even burn of the tobacco[37] and is used to ensure complete combustion of paper cartridges for cap and ball revolvers.[38] It can also be heated to several hundred degrees to be used for niter bluing, which is less durable than other forms of protective oxidation, but allows for specific and often beautiful coloration of steel parts, such as screws, pins, and other small parts of firearms.

Meat processing

[edit]Potassium nitrate has been a common ingredient of salted meat since antiquity[39] or the Middle Ages.[40] The widespread adoption of nitrate use is more recent and is linked to the development of large-scale meat processing.[6] The use of potassium nitrate has been mostly discontinued because it gives slow and inconsistent results compared with sodium nitrite preparations such as "Prague powder" or pink "curing salt". Even so, potassium nitrate is still used in some food applications, such as salami, dry-cured ham, charcuterie, and (in some countries) in the brine used to make corned beef (sometimes together with sodium nitrite).[41] In the Shetland Islands (UK) it is used in the curing of mutton to make reestit mutton, a local delicacy.[42] When used as a food additive in the European Union,[43] the compound is referred to as E252; it is also approved for use as a food additive in the United States[44] and Australia and New Zealand[45] (where it is listed under its INS number 252).[2]

Possible cancer risk

[edit]Since October 2015, WHO classifies processed meat as Group 1 carcinogen (based on epidemiological studies, convincingly carcinogenic to humans).[46]

In April 2023 the French Court of Appeals of Limoges confirmed that food-watch NGO Yuka was legally legitimate in describing Potassium Nitrate E249 to E252 as a "cancer risk", and thus rejected an appeal by the French charcuterie industry against the organisation.[47]

Fertilizer

[edit]Potassium nitrate is used in fertilizers as a source of nitrogen and potassium – two of the macronutrients for plants. When used by itself, it has an NPK rating of 13-0-44.[48][49]

Pharmacology

[edit]- Used in some toothpastes for sensitive teeth.[50] Recently,[when?] the use of potassium nitrate in toothpastes for treating sensitive teeth has increased.[51][52]

- Used historically to treat asthma.[53] Used in some toothpastes to relieve asthma symptoms.[54]

- Used in Thailand as main ingredient in kidney tablets to relieve the symptoms of cystitis, pyelitis and urethritis.[55]

- Combats high blood pressure and was once used as a hypotensive.[56]

Other uses

[edit]- Used as an electrolyte in a salt bridge.

- Active ingredient of condensed aerosol fire suppression systems. When burned with the free radicals of a fire's flame, it produces potassium carbonate.[57]

- Works as an aluminium cleaner.

- Component (usually about 98%) of some tree stump removal products. It accelerates the natural decomposition of the stump by supplying nitrogen for the fungi attacking the wood of the stump.[58]

- In heat treatment of metals as a medium temperature molten salt bath, usually in combination with sodium nitrite. A similar bath is used to produce a durable blue/black finish typically seen on firearms. Its oxidizing quality, water solubility, and low cost make it an ideal short-term rust inhibitor.[59]

- To induce flowering of mango trees in the Philippines.[60][61]

- Thermal storage medium in power generation systems. Sodium and potassium nitrate salts are stored in a molten state with the solar energy collected by the heliostats at the Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant. Ternary salts, with the addition of calcium nitrate or lithium nitrate, have been found to improve the heat storage capacity in the molten salts.[62]

- As a source of potassium ions for exchange with sodium ions in chemically strengthened glass.

- As an oxidizer in model rocket fuel called Rocket candy.

- As a constituent in homemade smoke bombs.[63]

In folklore and popular culture

[edit]Potassium nitrate was once thought to induce impotence, and is still rumored to be in institutional food (such as military fare). There is no scientific evidence for such properties.[64][65] In Bank Shot, El (Joanna Cassidy) propositions Walter Ballantine (George C. Scott), who tells her that he has been fed saltpeter in prison.[citation needed] In One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Randle is asked by the nurses to take his medications, but not knowing what they are, he mentions he does not want anyone to "slip me saltpeter". He then proceeds to imitate the motions of masturbation.

In 1776, John Adams asks his wife Abigail to make saltpeter for the Continental Army. She, eventually, is able to do so in exchange for pins for sewing.[66]

In the Star Trek episode "Arena", Captain Kirk injures a gorn using a rudimentary cannon that he constructs using potassium nitrate as a key ingredient of gunpowder.[citation needed]

In 21 Jump Street, Jenko, played by Channing Tatum, gives a rhyming presentation about potassium nitrate for his chemistry class.[citation needed]

In Eating Raoul, Paul hires a dominatrix to impersonate a nurse and trick Raoul into consuming saltpeter in a ploy to reduce his sexual appetite for his wife.[citation needed]

In The Simpsons episode "El Viaje Misterioso de Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Our Homer)", Mr. Burns is seen pouring saltpeter into his chili entry, titled Old Elihu's Yale-Style Saltpeter Chili.[citation needed]

In the Sharpe novel series by Bernard Cornwell, numerous mentions are made of an advantageous supply of saltpeter from India being a crucial component of British military supremacy in the Napoleonic Wars. In Sharpe's Havoc, the French Captain Argenton laments that France needs to scrape its supply from cesspits.[citation needed]

In the Dr. Stone anime and manga series, the struggle for control over a natural saltpeter source from guano features prominently in the plot.[citation needed]

In the farming lore from the Corn Belt of the 1800s, drought-killed corn[67] in manured fields could accumulate saltpeter to the extent that upon opening the stalk for examination it would "fall as a fine powder upon the table".[68]

In the Slovenian short story Martin Krpan from Vrh pri Sveti Trojici, the titular character and Slovene folk hero Martin Krpan illegally smuggles "English salt" for a living. The exact nature of "English salt" is a matter of debate, but it may have been a euphemism for potassium nitrate (saltpeter) due to its role in manufacturing gunpowder.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- History of gunpowder

- Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works

- Niter, a mineral form of potassium nitrate

- Nitratine

- Nitrocellulose

- Potassium perchlorate

References

[edit]- ^ Record of Potassium nitrate in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, accessed on 2007-03-09.

- ^ a b c B. J. Kosanke; B. Sturman; K. Kosanke; et al. (2004). "2". Pyrotechnic Chemistry. Journal of Pyrotechnics. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-889526-15-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05.

- ^ Kolthoff, Treatise on Analytical Chemistry, New York, Interscience Encyclopedia, Inc., 1959.

- ^ Ema, M.; Kanoh, S. (1983). "[Studies on the pharmacological bases of fetal toxicity of drugs. III. Fetal toxicity of potassium nitrate in 2 generations of rats]". Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica. 81 (6): 469–480. doi:10.1254/fpj.81.469. ISSN 0015-5691. PMID 6618340.

- ^ a b Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 9780199206872.

- ^ a b Lauer, Klaus (1991). "The history of nitrite in human nutrition: A contribution from German cookery books". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 44 (3): 261–264. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(91)90037-a. ISSN 0895-4356. PMID 1999685.

- ^ Haldane, J. (1901). "The Red Colour of Salted Meat". The Journal of Hygiene. 1 (1): 115–122. doi:10.1017/S0022172400000097. ISSN 0022-1724. PMC 2235964. PMID 20474105.

- ^ Spencer, Dan (2013). Saltpeter:The Mother of Gunpowder. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780199695751.

- ^ a b "Saltpetre | Definition, Uses, & Facts | Britannica". 3 May 2024.

- ^ Peter Watson (2006). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. HarperCollins. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1. Archived from the original on 2015-10-17.

- ^ Cathal J. Nolan (2006). The age of wars of religion, 1000–1650: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. Vol. 1 of Greenwood encyclopedias of modern world wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

In either case, there is linguistic evidence of Chinese origins of the technology: in Damascus, Arabs called the saltpeter used in making gunpowder "Chinese snow," while in Iran it was called "Chinese salt."

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1963). English artillery, 1326–1716: being the history of artillery in this country prior to the formation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Royal Artillery Institution. p. 42.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ a b James Riddick Partington (1999). A history of Greek fire and gunpowder. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Yu, Ping-Yu (1980). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts. Vol. 5. Contributors Joseph Needham, Lu Gwei-Djen, Nathan Sivin (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0521085731. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ^ Sen, Sudipta (2019). Ganges: The Many Pasts of an Indian River. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-300-11916-9.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2014). Military Transition in Early Modern Asia, 1400–1750. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-7809-3765-6.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources Archived 2008-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ Jack Kelly (2005). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-465-03722-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-11.

- ^ Major George Rains (1861). Notes on Making Saltpetre from the Earth of the Caves. New Orleans, LA: Daily Delta Job Office. p. 14. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Joshi, Chirag S.; Shukla, Manish R.; Patel, Krunal; Joshi, Jigar S.; Sahu, Omprakash (2014). "Environmentally and Economically Feasibility Manufacturing Process of Potassium Nitrate for Small Scale Industries: A Review". International Letters of Chemistry, Physics and Astronomy. 41: 88–99. doi:10.56431/p-je383z.

- ^ John Spencer Bassett; Edwin Mims; William Henry Glasson; et al. (1904). The South Atlantic Quarterly. Duke University Press. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Paul-Antoine Cap (1857). Etudes biographiques pour servir à l'histoire des sciences ...: sér. Chimistes. V. Masson. pp. 294–. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Oscar Gutman (1906). Monumenta pulveris pyrii. Repr. Artists Press Balham. pp. 50–.

- ^ Alexander Adam (1805). A compendious dictionary of the Latin tongue: for the use of public Seminar and private March 2012. Printed for T. Cachorro and W. Davies, by C. Stewart, London, Bell and Bradfute, W. Creech.

- ^ SP Dom Elizabeth vol.xvi 29–30 (1589)

- ^ Narihiro, Takashi; Tamaki, Hideyuki; Akiba, Aya; et al. (11 August 2014). "Microbial Community Structure of Relict Niter-Beds Previously Used for Saltpeter Production". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e104752. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j4752N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104752. PMC 4128746. PMID 25111392.

- ^ Ruane, Michael. "During the Civil War, the enslaved were given an especially odious job. The pay went to their owners". Washington Post. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b Joseph LeConte (1862). Instructions for the Manufacture of Saltpeter. Columbia, S.C.: South Carolina Military Department. p. 14. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ LeConte, Joseph (1862). Instructions for the Manufacture of Saltpetre. Charles P. Pelham, State Printer.

- ^ "How Refrigerators Work". HowStuffWorks. 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ^ a b c Adiwidjaja, G.; Pohl, D. (2003). "Superstructure of α-phase potassium nitrate". Acta Crystallographica Section C. 59 (12): i139–i140. Bibcode:2003AcCrC..59I.139A. doi:10.1107/S0108270103025277. PMID 14671340.

- ^ Nimmo, J. K.; Lucas, B. W. (1976). "The crystal structures of γ- and β-KNO3 and the α ← γ ← β phase transformations". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 32 (7): 1968–1971. doi:10.1107/S0567740876006894.

- ^ Freney, E. J.; Garvie, L. A. J.; Groy, T. L.; Buseck, P. R. (2009). "Growth and single-crystal refinement of phase-III potassium nitrate, KNO3". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 65 (6): 659–663. doi:10.1107/S0108768109041019. PMID 19923693.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Eli S. Freeman (1957). "The Kinetics of the Thermal Decomposition of Potassium Nitrate and of the Reaction between Potassium Nitrite and Oxygen". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (4): 838–842. doi:10.1021/ja01561a015.

- ^ Amthyst Galleries, Inc Archived 2008-11-04 at the Wayback Machine. Galleries.com. Retrieved on 2012-03-07.

- ^ Inorganic Additives for the Improvement of Tobacco Archived 2007-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, TobaccoDocuments.org

- ^ Kirst, W.J. (1983). Self Consuming Paper Cartridges for the Percussion Revolver. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Northwest Development Co.

- ^ Binkerd, E. F; Kolari, O. E (1975-01-01). "The history and use of nitrate and nitrite in the curing of meat". Food and Cosmetics Toxicology. 13 (6): 655–661. doi:10.1016/0015-6264(75)90157-1. ISSN 0015-6264. PMID 1107192.

- ^ "Meat Science", University of Wisconsin. uwex.edu.

- ^ Corned Beef Archived 2008-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Food Network

- ^ Brown, Catherine (2011-11-14). A Year In A Scots Kitchen. Neil Wilson Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781906476847.

- ^ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Archived from the original on 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration: "Listing of Food Additives Status Part II". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2011-11-08. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code "Standard 1.2.4 – Labelling of ingredients". 8 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ Rabino, Thomas (13 April 2023). "Nitrites et jambons "cancérogènes" : nouvelle victoire en appel de Yuka contre un industriel de la charcuterie" [Nitrites and "carcinogenic" hams: Yuka's new appeal victory against a charcuterie manufacturer]. Marianne (in French).

Et ce, en dépit de la multiplicité des avis scientifiques, comme celui du Centre international de recherche sur le cancer, classant ces mêmes additifs, connus sous le nom de E249, E250, E251, E252, parmi les « cancérogènes probables », auxquels la Ligue contre le cancer attribue près de 4 000 cancers colorectaux par an.

[And this, despite the multiplicity of scientific opinions, such as that of the International Agency for Research on Cancer, classifying these same additives, known as E249, E250, E251, E252, among the "probable carcinogens", to which the League Against Cancer attributes nearly 4,000 colorectal cancers per year.] - ^ Michigan State University Extension Bulletin E-896: N-P-K Fertilizers Archived 2015-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hall, William L; Robarge, Wayne P; Meeting, American Chemical Society (2004). Environmental Impact of Fertilizer on Soil and Water. American Chemical Society. p. 40. ISBN 9780841238114. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27.

- ^ "Sensodyne Toothpaste for Sensitive Teeth". 2008-08-03. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Enomoto, K; et al. (2003). "The Effect of Potassium Nitrate and Silica Dentifrice in the Surface of Dentin". Japanese Journal of Conservative Dentistry. 46 (2): 240–247. Archived from the original on 2010-01-11.

- ^ R. Orchardson & D. G. Gillam (2006). "Managing dentin hypersensitivity" (PDF). Journal of the American Dental Association. 137 (7): 990–8, quiz 1028–9. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0321. PMID 16803826. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-29.

- ^ Orville Harry Brown (1917). Asthma, presenting an exposition of the nonpassive expiration theory. C.V. Mosby company. p. 277.

- ^ Joe Graedon (May 15, 2010). "'Sensitive' toothpaste may help asthma". The Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ "Local manufactured drug registration for human (combine) – Zoro kidney tablets". fda.moph.go.th. Thailand. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014.

Potassium nitrate 60mg

- ^ Reichert ET. (1880). "On the physiological action of potassium nitrite". Am. J. Med. Sci. 80: 158–180. doi:10.1097/00000441-188007000-00011.

- ^ Adam Chattaway; Robert G. Dunster; Ralf Gall; David J. Spring. "The evaluation of non-pyrotechnically generated aerosols as fire suppressants" (PDF). United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-29.

- ^ Stan Roark (February 27, 2008). "Stump Removal for Homeowners". Alabama Cooperative Extension System. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ David E. Turcotte; Frances E. Lockwood (May 8, 2001). "Aqueous corrosion inhibitor Note. This patent cites potassium nitrate as a minor constituent in a complex mix. Since rust is an oxidation product, this statement requires justification". United States Patent. 6,228,283. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018.

- ^ Elizabeth March (June 2008). "The Scientist, the Patent and the Mangoes – Tripling the Mango Yield in the Philippines". WIPO Magazine. United Nations World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Archived from the original on 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Filipino scientist garners 2011 Dioscoro L. Umali Award". Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA). Archived from the original on 30 November 2011.

- ^ Juan Ignacio Burgaleta; Santiago Arias; Diego Ramirez. "Gemasolar, The First Tower Thermosolar Commercial Plant With Molten Salt Storage System" (PDF) (Press Release). Torresol Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ "How to Make the Ultimate Colored Smoke Bomb". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ^ "The Straight Dope: Does saltpeter suppress male ardor?". 1989-06-16. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Richard E. Jones & Kristin H. López (2006). Human Reproductive Biology, Third Edition. Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-12-088465-0. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- ^ "10 reasons true Americans should watch '1776' this 4th of July". EW.com. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- ^ Krug, E.C.; Hollinger, S.E. (2003), Identification of factors that aid carbon sequestration in Illinois agricultural systems (PDF), Champaign, Illinois: Illinois State Water Survey, Atmospheric Environment Section, pp. 27–28, retrieved 2022-03-13

- ^ Mayo, N.S. (1895), Cattle poisoning by nitrate of potash (PDF), Manhattan: Kansas State Agricultural College, p. 5, retrieved 2022-03-13

Bibliography

[edit]- Barnum, Dennis W. (December 2003). "Some History of Nitrates". Journal of Chemical Education. 80 (12): 1393. Bibcode:2003JChEd..80.1393B. doi:10.1021/ed080p1393.

- David Cressy. Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder (Oxford University Press, 2013) 237 pp online review by Robert Tiegs

- Alan Williams. "The production of saltpeter in the Middle Ages", Ambix, 22 (1975), pp. 125–33. Maney Publishing, ISSN 0002-6980.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XXI (9th ed.). 1886. p. 235.

- International Chemical Safety Card 018402216