Jiang Qing

Jiang Qing | |

|---|---|

江青 | |

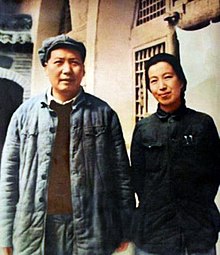

Jiang in 1976 | |

| Spouse of the Paramount leader of China | |

| In office 1 October 1949 – 9 September 1976 | |

| Leader | Mao Zedong (party chairman) |

| Succeeded by | Han Zhijun |

| Spouse of the President of China | |

| In office 27 September 1954 – 27 April 1959 | |

| President | Mao Zedong |

| Succeeded by | Wang Guangmei |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Li Shumeng March 1914 Zhucheng, Shandong, Republic of China |

| Died | 14 May 1991 (aged 77) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Cause of death | Suicide by hanging |

| Resting place | Beijing Futian Cemetery |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Li Na |

| Criminal penalty | Death sentence with reprieve, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Signature |  |

| Jiang Qing | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 江青 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Jiang Qing[note 1] (March 1914 – 14 May 1991), also known as Madame Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary, actress, and political figure. She was the fourth wife of Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Communist Party and Paramount leader of China. Jiang was best known for playing a major role in the Cultural Revolution as the leader of the radical Gang of Four.

Born into a declining family with an abusive father and a mother whose work as a domestic servant and sometimes a prostitute, Jiang Qing rose above her beginnings to become a renowned actress in Shanghai, and later the wife of Mao Zedong, in the 1930s.[1] In the 1940s, she worked as Mao Zedong's personal secretary, and during the 1950s, she headed the Film Section of the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Appointed deputy director of the Central Cultural Revolution Group in 1966, Jiang played a pivotal role as Mao’s emissary during the early stages of the Cultural Revolution. Collaborating with Lin Biao, she advanced Mao’s ideology and promoted his cult of personality. Jiang wielded considerable influence over state affairs, particularly in culture and the arts. Propaganda posters idolised her as the "Great Flagbearer of the Proletarian Revolution." In 1969, she secured a seat on the Politburo, cementing her power.

Following Mao's death, she was soon arrested by Hua Guofeng and his allies in 1976. State media portrayed her as the "White-Boned Demon,"[1][2] and she was widely blamed for instigating the Cultural Revolution, a period of upheaval that caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Chinese people. Initially sentenced to death, Jiang's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1983. Released for medical treatment in the early 1990s, she committed suicide in May 1991.[3][4]

Names

[edit]Chinese names

[edit]Jiang Qing was known by various names throughout her life. Before her birth, her father named the baby Li Jinnan,[b] where Jinnan means the "coming boy." When she was born, her father changed the name to Li Jinhai,[c] meaning the "coming child."[5] Therefore, Jiang Qing also called herself Li Jin.[d][5][6] Several other sources indicate her birth name Li Shumeng,[e][7][8] which means "pure and simple."[8][9]

She adopted the name Li Yunhe[f] during primary school.[10][5] She told her biographer Roxane Witke that she liked the name because "Yunhe," meaning "crane in the cloud," sounded beautiful.[10] In July 1933, during her first visit to Shanghai, she assumed the name Li He[g] and worked as a teacher for local workers. On her second visit to Shanghai in June 1934, she used the alias Zhang Shuzhen.[h] Later, when detained by the Nationalist government in October 1934, she identified herself as Li Yungu.[i][5]

In 1935, when she entered the entertainment industry, she took on the stage name Lan Pin,[j] which means "blue apple".[11][12] Although the name had no particular meaning, its bluntness made it unique. However, Jiang Qing did not favour this name due to its association with her scandals in Shanghai.[13] She became known as Jiang Qing upon arriving in Yan'an, where "Jiang" means "river" and "Qing" means "azure" or "better than blue".[14]

In 1991, when she was hospitalised in Beijing, she used the name Li Runqing.[k] When she died in Beijing, her body was labelled with the pseudonym Li Zi.[l] In March 2002, she was buried in Beijing by the name Li Yunhe.[15][16]

English names

[edit]In English, many contemporary articles used the Wade–Giles romanisation system to spell Chinese names. For this reason, some sources – especially older ones – spell her name "Chiang Ch'ing".[17] She was also known as Madame Mao, as the wife and widow of Mao Zedong.[18]

Early life

[edit]Jiang Qing was born in Zhucheng, Shandong, in March 1914. She deliberately kept her exact birth date private to avoid receiving any gifts.[14] Her father was Li Dewen[m], a carpenter, and her mother, whose name is unknown,[19] was Li's subsidiary wife, or concubine.[20] Her father had his own carpentry and cabinet making workshop.[19] Her parents were married after her father found his first wife unable to conceive.[21]

As a child, Jiang was deeply traumatised by the domestic violence inflicted by her father, who verbally and physically abused her mother almost every day. One Lantern Festival, after her father broke her mother’s finger during an attack, her mother fled with Jiang under the cover of darkness.[21][22] Her mother found work as a domestic servant that often blurred the lines with prostitution, [23] and her husband separated from her.[24]

Jiang eventually moved with her mother to her grandparents' home in Jinan. However, they soon returned to Zhucheng, as her mother continued to seek inheritance rights, or financial support, from her husband’s family, which proved extremely difficult. During this period, Jiang attended two primary schools with disruptions, where she was often mocked for wearing outdated, boyish clothing from her brothers. She became silent and not easy to open up.[25]

Her mother, having fallen ill, eventually abandoned hope of obtaining further financial support from her husband. After selling some of her belongings, she purchased a train ticket, and together with Jiang, boarded a train from Jiaoxian to Jinan. There, Jiang was welcomed by her grandparents and resumed her primary education.[26] In 1926–1927, her mother took her further north to Tianjin to stay with her half-sister. During this time, Jiang worked as a housekeeper in the household. She proposed taking a job rolling cigarettes, but the family disapproved. Later they returned to Jinan, where her mother passed away in 1928.[27]

Entertainment career

[edit]Jinan

[edit]At 14, Jiang, now an orphan, joined a local underground theatre troupe, seeking independence. Her striking looks drew attention, but she remained sensitive about her poor upbringing. Alarmed by her undisclosed departure, her grandparents paid the troupe's boss to bring her back. She enrolled in the Experimental Arts Academy, which became less picky about the social class of new entrants due to the May Fourth Movement. Despite her strong Shandong accent initially hindering her performances, she excelled during her year of training, in some traditional opera roles. When the academy closed in 1930, Jiang, though only half-trained, was chosen to join theatrical companies in Beijing.[28] She returned to Jinan in May 1931 and married Pei Minglun,[n] the wealthy son of a businessman, and soon divorced.[28][31]

Qingdao

[edit]Following her divorce, Jiang reached out to Zhao Taimou, the former director of the Arts Academy and dean of Qingdao University. With the assistance of Zhao's wife, Yu Shan, Jiang secured a position as a clerk in the university library.[32] Yu Shan later introduced Jiang to her brother, Yu Qiwei,[33] an upper-class youth who had embraced the Communist cause and was connected to underground Communist organisations as well as literary and performing arts circles.[34] In 1932, Jiang and Yu Qiwei fell in love and began living together, enabling Jiang to gain entry into the Communist Cultural Front.[34] She became a member of the Seaside Drama Society, performing in plays such as Lay Down Your Whip, harnessing the influence of theatre to resist Japanese aggression. In February 1933, she officially joined the CCP.[35]

Shanghai

[edit]Yu was arrested in April the same year and Jiang was subsequently shunned by his family. She fled to her parents' home and returned to the drama school in Jinan. Through friendships she had previously established, she received an introduction to attend Shanghai University for the summer where she also taught some general literacy classes. In October, she rejoined the Communist Youth League and, at the same time, began participating in an amateur drama troupe.[36]

Jiang was among the cast of a production of Roar, China! which British authorities banned from being performed in Shanghai's International Settlement.[37]In September 1934, Jiang was arrested and jailed for her political activities in Shanghai, but was released three months later, in December of the same year.[36] She then traveled to Beijing where she reunited with Yu Qiwei who had just been released following his prison sentence, and the two began living together again.[36]

Jiang returned to Shanghai in March 1935 and became a professional actress, adopting the stage name "Lan Ping". She appeared in numerous films and plays, including Goddess of Freedom, Scenes of City Life, Blood on Wolf Mountain and Wang Laowu. In Ibsen's play A Doll's House, Jiang played the role of Nora.[38]

| Year | English title | Original title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1935 | Goddess of Freedom | 自由神 | Yu Yueying | |

| Scenes of City Life | 都市风光 | Wang Junsheng's girlfriend | ||

| 1936 | Blood on Wolf Mountain | 狼山喋血记 | Liu Sansao | |

| 1937 | Lianhua Symphony | 联华交响曲 | Rickshaw puller's wife | Segment 1: "Twenty Cents" |

| 1938 | Wang Laowu | 王老五 | Young Girl Li | Filmed in 1937. Leading actress |

Early political activities

[edit]

Following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident on 7 July 1937, and the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, which destroyed most of its movie industry, Jiang left her celebrity life on the stage behind. She went first to Xi'an, then to the Chinese Communist headquarters in Yan'an to "join the revolution" and the war to resist the Japanese invasion. In November, she enrolled in the "Counter-Japanese Military and Political University" (Marxist–Leninist Institute) for study. The Lu Xun Academy of Arts was newly founded in Yan'an on 10 April 1938, and Jiang became a drama department instructor, teaching and performing in college plays and operas.[39][40]

Marriage with Mao Zedong

[edit]Shortly after arriving in Yan'an, Jiang became involved with Mao Zedong. Some communist leaders were scandalized by the relationship once it became public. At 45, Mao was nearly twice Jiang's age, and Jiang had lived a highly bourgeois lifestyle before coming to Yan'an. Mao was still married to He Zizhen, a lifelong Communist who had previously completed the Long March with him, and with whom Mao had five children. Eventually, Mao arranged a compromise with the other leaders of the CCP: Mao was granted a divorce and permitted to marry Jiang, but she was required to stay out of public politics for twenty years. Jiang abided by this agreement. However, thirty years later, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Jiang became active in politics.[40]

On 28 November 1938, Jiang and Mao married in a small private ceremony following approval by the Party's Central Committee. Because Mao's marriage to He had not yet ended, Jiang was reportedly made to sign a marital contract which stipulated that she would not appear in public with Mao as her escort. Jiang and Mao's only child together, a daughter named Li Na, was born in 1940.[40]

First Lady

[edit]

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Jiang became the nation's first lady. Jiang was the deputy director of the Film Guidance Committee, which evaluated all movie projects from 1949 to 1951.[41] An uproar in 1950 led to the investigation of The Life of Wu Xun, a film about a 19th-century beggar who raised money to educate the poor. Jiang supported criticism of the film for celebrating counter-revolutionary ideas.[citation needed]

Jiang was ill for much of the 1950s, and while ill she stepped back from her official role.[42] Jiang recovered from cervical cancer in 1957. Jiang thought herself still ill, while her doctors believed she was in good health.[42] They therefore recommended that she enjoy movies, music, theater, and concerts as a form of therapy.[42]

Following the Great Leap Forward (1958–62), Mao was highly criticized within the CPC, and turned to Jiang, among others, to support him and persecute his enemies. After Mao wrote a pamphlet questioning the persistence of "feudal and bourgeois" traditional opera, Jiang took this as a license to systematically purge Chinese media and literature of everything but political propaganda. The result ended up being a near-total suppression of all creative works in China aside from rigidly-prescribed "revolutionary" material.[citation needed]

In her first public speech in June 1964 at a Peking Opera convention, Jiang criticized regional opera troupes for glorifying emperors, generals, scholars, and other ox-demons and snake-spirits.[43]

In February 1966, Jiang hosted a forum with PLA officers.[44] The group studied writings by Mao, watched films and plays, and met with the cast and crew of an in-progress film production.[44] The forum concluded that a "black line" of bourgeois thought dominated the arts since the PRC's founding.[45] A summary of Jiang's analysis at the forum was later distributed widely during the Cultural Revolution and became a significant document.[46]

Over April through June 1966, Jiang presided over the All-Army Artistic Creation Conference in Beijing.[46] Conference attendees evaluated a total of 80 domestic and foreign films.[46] Jiang approved of 7 as consistent with Mao Zedong Thought and criticized the other films.[46]

Cultural Revolution

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Maoism |

|---|

|

Backed by her husband, she was appointed deputy director of the Central Cultural Revolution Group (CCRG) in 1966 and emerged as a serious political figure in the summer of that year.[47] At the 9th Party Congress in April 1969, she was elevated to the Politburo. By then, she had established a close political working relationship with the other members of what later became known as the Gang of Four: Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan and Wang Hongwen.[48]

During this period, Mao galvanized students and young workers as his paramilitary organization the Red Guards to attack what he termed as revisionists in the party. Mao told them the revolution was in danger and that they must do all they could to stop the emergence of a privileged class in China. He argued this is what had happened in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev.[48]

With time, Jiang began playing an increasingly active political role in the movement. She took part in most important Party and government activities. She was supported by a radical coterie, dubbed, by Mao himself, the Gang of Four. Although a prominent member of the Central Cultural Revolution Group and a major player in Chinese politics from 1966 to 1976, she essentially remained on the sidelines.[3]

The initial storm of the Cultural Revolution came to an end when President Liu Shaoqi was forced from all his posts on 13 October 1968. Lin Biao now became Mao's designated successor. Chairman Mao now gave his support to the Gang of Four. These four radicals occupied powerful positions in the Politburo after the Tenth Party Congress of 1973.[citation needed]

When traditional landscape and bird-and-flower paintings re-emerged in the early 1970s, Jiang criticized these traditional forms as "black paintings".[49]: 166

Jiang first collaborated with then second-in-charge Lin Biao, but after Lin Biao's death in 1971, she turned against him publicly in the Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius Campaign. By the mid-1970s, Jiang also spearheaded the campaign against Deng Xiaoping (afterwards saying that this was inspired by Mao). The Chinese public became intensely discontented at this time and chose to blame Jiang, a more accessible and easier target than Chairman Mao.[50] By 1973, although unreported due to it being a personal matter, Mao and his wife Jiang had separated:

It was reported that Mao Tsetung and Chiang Ching were separated in 1973. Most people, however, did not know this. Hence Chiang Ching was still able to use her position as Mao's wife to deceive people. Because of her relations to Mao, it was particularly difficult for the Party to deal with her.[51]

Jiang's hobbies included photography, playing cards, and holding screenings of classic Hollywood films, especially those featuring Greta Garbo, one of her favorite actresses, even as they were banned for the average Chinese citizen as a symbol of bourgeois decadence.[52] When touring a troupe of young girls excelling in marksmanship, she discovered Joan Chen, then 14 years old, launching Joan's career as a Chinese and then international actress.[53]

Shaping of Chinese Socialist Opera

[edit]In 1967, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Jiang declared eight works of performance art to be the new models for proletarian literature and art.[54] These "model operas", or "revolutionary operas", were designed to glorify Mao Zedong, The People's Liberation Army, and the revolutionary struggles. The ballets White-Haired Girl,[55] Red Detachment of Women, and Shajiabang ("Revolutionary Symphonic Music") were included in the list of eight, and were closely associated with Jiang, because of their inclusion of elements from Chinese and Western opera, dance, and music.[56] During Richard Nixon's famous visit to China in February 1972, he watched Red Detachment of Women, and was impressed by the opera. He famously asked Jiang who the writer, director, and composer were, to which she replied it was "created by the masses."[57]

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, theater reform was high on the agenda for the new Communist government as the Theater Reform Bureau (Xi Gai Ju) was established on Oct 2nd. However, the bureau was disbanded a year after due to widespread protests by performing artists, who referred to the bureau as "Theater Slaughter Bureau" (Xi Zai Ju). In 1950, with the creation of the first national theater academy, premier Zhou Enlai announced a new theater reform policy that aimed to politically indoctrinate the performing artists and nationalize opera companies.[58]

In 1951, Jiang Qing was given a minor position of Film Bureau Chief. After her appointment, Jiang engaged in three attempts in establishing the standard for socialist art. Jiang's first attempt was her advice to ban the 1950 Hong Kong movie The Inside Story of the Qing Dynasty Court (Qinggong Mishi), of which Jiang believed to be unpatriotic. Her opinion was not taken seriously by the communist leadership due to the minor political influence of her office and the movie was distributed in PRC's major cities like Beijing and Shanghai.[59] Despite the difficulties to have her opinion recognized by the communist leadership, Jiang was able to rely on Mao's influence to support her position within the party. Four years after the airing of The Inside Story of the Qing Dynasty Court, Mao pointed out in a letter to the top leaders that "we haven't criticized Inside Story yet", echoing Jiang's criticisms. Later in 1951, Jiang critiqued and objected to the distribution of the movie The Story of Wu Xun (Wu Xun Zhuan) for glorifying the wealthy landed class while dismissing the peasantry. Again, Jiang's opinion was dismissed by the communist leadership due to the lack of political influence from her office. However, Mao intervened for the second time as he penned the article "We Need to Pay Attention to the Discussion of the Movie The Story of Wu Xun" and published it on May 20, 1951, in The People's Daily. Mao criticized the movie for portraying and endorsing Wu Xun as anti-revolutionary. Nonetheless, Jiang's third attempt involved the role of literary criticism in the development of socialist art. She asked the editor of The People's Daily to republish the new literary interpretation of the classic novel Dream of Red Mansions (Hong Lou Meng) by two young scholars at Shandong University. The editor refused Jiang's request on the grounds that the party newspaper was not a forum for free debate. Again, Mao spoke up on Jiang's behalf.[59]

Jiang would spend 1955–1962 in Moscow for medical treatments. However, during this period, as a foreign dignitary, Jiang was able to access a wide variety of movies that were banned in Soviet Russia, including many Hollywood productions. With such access, Jiang was able to stay informed of the western art trends, which would go on to shape her transformation of the Beijing Opera House.[58]

After Jiang's return to China in 1962, she frequently attended local opera performances. In 1963, Jiang asked A Jia, the director of the National Beijing Opera Company, to assist her in transforming the works of Beijing Opera with the modern revolutionary socialist theme. She would later ask the Beijing Municipal Opera Company to develop the opera Among the Reeds (Shajiabang) featuring the struggle between the Nationalists and Communists during the Second Anti-Japanese War (1937-1945). She was also behind the development of the opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (Zhiqu Weihu Shan), which she tasked the Shanghai Beijing Opera Company for the production. In July 1964, Jiang Qing delivered the speech "On The Revolution of Beijing Opera" at the "Forum of Theatrical Workers Participating in the Festival of Peking Opera on Contemporary Themes." In her speech, Jiang expressed her discontent with how the "socialist country led by the Communist Party, the dominant position on the stage is not occupied by the workers, peasants, and soldiers, who are the real creators of history and the true masters of our country." Jiang noted that the majority of the opera stage in China were still occupied by scholars, royalties, ministers, and beauties, which she collectively categorized as "ancient Chinese and foreign figures." Jiang also criticized Beijing Opera for its use of "artistic exaggeration" that "has always depicted ancient times and people belonging to those times."[60] Jiang considered these ancient characters as negative. According to Jiang, the continuous portrayal of these negative characters made it hard to produce any positive figures, which are "characters of advanced revolutionary heroes." She used the example of the opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy to show that the change in the protagonist's portrayal was related to how "the roles of the People's Liberation Army men Yang Tzu-jung and Shao Chien-po have been made more prominent." Jiang also argued that the portrayal of positive characters was important as "good people are always the great majority" and that the productions should "educate and inspire the people and lead them forward", suggesting that many of the existing works must be revised to portray the masses.[60]

During the 1964 "Modern Beijing Opera Trial Performance Convention", Jiang's new productions, including the Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, were highly praised by the Communist leadership. These works helped her to establish her reputation in China's artistic realm and her plans to transform the Beijing Opera House. In June 1965, Jiang met and formed a working relationship with Yu Huiyong, the future Minister of Culture of the PRC. Jiang considered their ideas on the reformation of Beijing Opera to be "in total harmony." Jiang's considerable political power allowed Yu to push the yangbanxi (model drama) projects to fruition. She first arranged for Yu to join the composition team of her opera On the Docks, which was the first Beijing Opera to portray the themes from contemporary society and the lives of Shanghai's working class after liberation. Jiang also tasked Yu to revise the musical scores of the yangbanxi for the modern Chinese masses, and both of them believed that the revolutionary artwork must represent the reality of modern life.[59]

During the Cultural Revolution, The Red Guards condemned Yu to be a "bad element" for propagating feudalism through his utilization of traditional Chinese music in operas. Yu was also tagged as "a democrat hiding under the banner of the Communist Party" due to his frequent absences in party meetings. In 1966, Yu was subsequently sent to a Cow Shed, a small room where the "bad elements" were confined. In October 1966, Yu was released after Jiang requested a meeting with Yu to stage the production of two operas in Beijing. Jiang seated Yu next to her, as a display of Yu's importance in the making of yangbanxi, during the showing of Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.[59]

During the production of yangbanxi, Jiang had shown keen intuition, due to her experience as an actress, in showing the shape yangbanxi should take. However, Jiang's directions on opera reforms were often vague. Yu, acting as the pawn of Jiang, was able to manifest Jiang's orders into technical details that can be followed by the performers. Despite Yu's growing influence, he was never able to defy Jiang's orders, as he could only influence her thinking.[58]

Jiang identified the weakness of Beijing opera as the lack of well organized music, which according to Jiang, "builds the image of the characters." This conception was influenced by Yu's writing on the functional conception of music. Yu focused on reforming the language of music. This was due to Yu's belief that for yangbanxi to become successful in educating the masses on the structure and benefits of the new socialist state, the language of the music must be understandable to the common person. He first recommended that the lyrics be written in Mandarin, which was in line with the Chinese government policy that mandated the use of Mandarin as the language of instruction in schools nationwide. Yu also advocated that "the melody should be composed in such a way that it also shadowed the syllabic tonal patterns", which "should sound natural to the ear as well as being easily understandable to the listener."[59]

According to Jiang's theory of the "three prominences," the model revolutionary works were to foreground the principal hero over other heroic characters and positive characters over other characters. Jiang criticized spy thrillers (which were known as counterespionage films) for making the antagonists seem too intriguing.[61]

Jiang was known to be blunt in directing the yangbanxi, but Yu was able to serve as the mediator between Jiang and the performers. Since Jiang could not communicate her vision clearly, performers often take her criticisms as personal insults. Du Mingxin, one of Jiang's composers, recalled Jiang dismissed his music in the ballet The Red Detachment of Women (Hong Se Niang Zi Jun) as "erotic ballad that used to be performed in the 1930s Shanghai nightclubs". Du was then criticized for trying to destroy the yangbanxi project by hiding bourgeois music in a revolutionary ballet. Du felt humiliated by this remark. It was until Yu asked the group to submit another composition that Du regained his motivation and composed the now famous Wanquan Heshui (On Wanquan River). According to Du, this incident revealed Yu's artistic integrity, personal courage, and the ability to gain Jiang's acknowledgement on his decisions.[59]

Political persecution of enemies

[edit]Jiang took advantage of the Cultural Revolution to wreak vengeance on her personal enemies, including people who had slighted her during her acting career in the 1930s. She incited radical youths organized as Red Guards against other senior political leaders and government officials, including Liu Shaoqi, the President at the time, and Deng Xiaoping, the Vice Premier. Internally divided into factions both to the "left" and "right" of Jiang and Mao, not all Red Guards were friendly to Jiang.[citation needed]

Jiang's rivalry with, and personal dislike of, Zhou Enlai led Jiang to hurt Zhou where he was most vulnerable. In 1968, Jiang had Zhou's adopted son (Sun Yang) and daughter (Sun Weishi) tortured and murdered by Red Guards. Sun Yang was murdered in the basement of Renmin University. After Sun Weishi died following seven months of torture in a secret prison (at Jiang's direction), Jiang made sure that Sun's body was cremated and disposed of so that no autopsy could be performed and Sun's family could not have her ashes. In 1968, Jiang forced Zhou to sign an arrest warrant for his own brother. In 1973 and 1974, Jiang directed the "Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius" campaign against premier Zhou because Zhou was viewed as one of Jiang's primary political opponents. In 1975, Jiang initiated a campaign named "Criticizing Song Jiang, Evaluating the Water Margin", which encouraged the use of Zhou as an example of a political loser. After Zhou Enlai died in 1976, Jiang initiated the "Five Nos" campaign in order to discourage and prohibit any public mourning for Zhou.[62]

Death of Mao Zedong

[edit]

On 5 September 1976, Mao's failing health turned critical when he suffered a heart attack, far more serious than his previous two earlier in the year.

Mao's death occurred just after midnight at 00:10 hours on 9 September 1976.

By this time, state media was effectively under the control of the Gang of Four. State newspapers continued to denounce Deng shortly after Mao's death. Jiang was little-concerned about the weak Hua Guofeng, but she feared Deng Xiaoping greatly. In numerous documents published in the 1970s, it was claimed that Jiang was conspiring to make herself the new Chairman of the Communist Party.[63]

Downfall

[edit]1976 Beijing coup

[edit]Hua Guofeng was Mao's chosen successor and became acting CCP chairman and acting premier after Mao's death;[64] Mao may have advised Hua to "consult Jiang if anything happens"[65] but in practice Hua became embroiled in a power struggle with the Gang of Four. On 6 October 1976, Hua – supported by the military and state security – had Jiang and the rest of the Gang arrested and removed from their party positions. According to Zhang Yaoci, who carried out the arrest, Jiang did not say much when she was arrested. It was reported that one of her servants spat at her as she was being taken away under a flurry of blows by onlookers and police.[66]

Hua was replaced by Deng Xiaoping, who proceeded with persecuting Jiang. She was tried starting in late 1980 with the other three members of the Gang of Four and six associates. At the time of her arrest, the country lacked the proper institutions for a legal trial.[67]

Televised trial

[edit]

In November 1980, the government announced that Jiang and nine others would stand trial. Jiang argued to the special prosecution teams that Mao should also be held accountable for her actions. Xinhua News Agency reported that Jiang initially sought to recruit her own lawyers but rejected those recommended by the special team after interviews. Meanwhile, five of the ten defendants agreed to be represented by government-appointed lawyers who would act as their defence counsel.[68]

As a result she and the other members of the Gang of Four were held in a state of limbo for the first six months of their capture. Following prompt legal modernization, an indictment was brought forward, formally titled "Indictment of the Special Procuratorate under the Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China.” The indictment contained 48 separate counts. She was accused of persecuting artists during the Cultural Revolution, and authorizing the burgling of the homes of writers and performers in Shanghai to destroy material related to Jiang's early career that could harm her reputation. Jiang was defiant. Whenever a witness took the stand, there was a chance the court proceedings would devolve into a shouting match.[67] She did not deny the accusations,[64] and insisted that she had been protecting Mao and following his instructions. Jiang remarked:[69]

I was Chairman Mao's dog. I bit whomever he asked me to bite.

Her defence strategy was marked by attempts to transcend the court room and appeal to history and the logic of revolution. The court announced its verdict after six weeks of testimony and debate and four weeks of deliberations. In early 1981, she was convicted and sentenced to death with a two year reprieve. She was assigned the highest level of criminal liability among the defendants as a "ringleader" of a counterrevolutionary group. Wu Xiuquan recounted in his memoir that the court room erupted into applause as the verdict was read and Qing was dragged out of the court room by two female guards while shouting revolutionary slogans.[67]

The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1983.[64] The Supreme People's Court determined that both Jiang and her chief associate, Zhang, had demonstrated "sufficient repentance" during their two-year reprieve, leading to their death sentences being commuted. However, senior Chinese officials have recently stated that Jiang has not shown genuine remorse and remains as defiant as the day she was removed from a crowded courtroom, shouting, "Long Live the Revolution."[70]

Death

[edit]Jiang was imprisoned at Qincheng Prison. She developed laryngeal cancer in the mid-1980s after which she was transferred from prison to house arrest. The cancer was treated at the Public Security Hospital.

On 14 May 1991,[23] at the hospital[71] she committed suicide by hanging; the suicide note read: "Today the revolution has been stolen by the revisionist clique of Deng, Peng Zhen, and Yang Shangkun. Chairman Mao exterminated Liu Shaoqi, but not Deng, and the result of this omission is that unending evils have been unleashed on the Chinese people and nation. Chairman, your student and fighter is coming to see you!"[23] The Chinese government confirmed her suicide on 4 June, withholding the announcement for two weeks to avoid its impact on the second anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement.[72][73]

Jiang was buried in Futian Cemetery in the western hills of Beijing. The grave marker is a tall white stone inscribed with her school name, and reads: "Tomb of Late Mother, Li Yunhe, 1914–1991". The cemetery was chosen for safety; the state refused her wish to be buried in Shandong, her home province, out of concerns over vandalism.[74]

Public image

[edit]After Jiang Qing’s arrest in 1976, the Chinese government launched a massive propaganda campaign to vilify her and the other members of the so-called Gang of Four. Orchestrated under the authoritarian political culture of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng, this campaign aimed to discredit Jiang and her associates entirely. In the years leading to her trial in 1980, millions of posters and cartoons depicted the Gang of Four as class enemies and spies. Jiang herself became the primary target of ridicule, portrayed as an empress scheming to succeed Mao and as a prostitute, with references to her past as a Shanghai actress used to question her moral integrity. The propaganda also criticised her interest in Western pastimes, such as photography and poker, portraying them as evidence of her lack of communist values. Ultimately, she was branded the "white-boned demon," a gendered caricature symbolising destruction and chaos.[75]

The 1980 Gang of Four trial solidified Jiang’s image as a manipulative and villainous figure. The indictment held the Gang responsible for the violence of the Cultural Revolution, accusing Jiang of using political purges for personal vendettas and fostering large-scale chaos. Widely broadcast both within and outside China, the trial reinforced a clear dichotomy: Jiang as a symbol of the past’s chaos, and Deng Xiaoping’s administration as the harbinger of order and progress. This narrative was consistent with the CCP’s Resolution on CPC History (1949–1981), which sought to redefine Mao Zedong’s legacy. While Mao was criticised for "errors," he was not held directly accountable for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. Instead, full blame was shifted to Jiang and the Gang of Four, allowing Mao Zedong Thought to remain ideologically valid under Deng’s reforms.[75]

Biographical literature on Jiang Qing has emerged as a tool to critique and reinterpret official Chinese historiography. These works challenge the one-dimensional vilification of Jiang, contributing to broader historical debates about the Cultural Revolution and its impact on shaping modern China. While factual biographies aim to deliver an accurate portrayal of their subject, fictional works take creative liberties, reimagining the life of a historical figure without strict adherence to facts. By rejecting the traditional authoritative biographical model—which presents a subject’s life as a coherent narrative—works such as Jiang Qing and Her Husbands and Becoming Madame Mao instead question the validity of totalising narratives about Jiang. Ultimately, the private sphere in these narratives is used not to provide more intimate insights into the subject but as a means to deconstruct and challenge official Chinese historiography.[75]

In popular culture

[edit]Writings

[edit]- Jiang Qing and Her Husbands, a 1990 Chinese historical play written by Sha Yexin

- Becoming Madame Mao, a 2000 historical novel by Anchee Min[76]

Movies and TV opera

[edit]| Year | Region | Name | Actress |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Taiwan | Fragrant Flower Versus Noxious Grass | Yao Hsiao-Chang |

| 1993 | China | China has a Mao Zedong | Zhang An'an |

| 2009 | China | The Founding of a Republic | Zhang Erdan |

| The Liberation | Yan Xuejing | ||

| Australia | Mao's Last Dance | Yue Xiuqing | |

| 2013 | China | Mao Zedong | Sun Jia |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]Translation notes

[edit]- ^ Chinese: 江青; pinyin: Jiāng Qīng; Wade–Giles: chiang ch'ing

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李进男; traditional Chinese: 李進男; pinyin: Lǐ Jìnnán; Wade–Giles: li3 chin4 nan2

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李进孩; traditional Chinese: 李進孩; pinyin: Lǐ Jìnhái; Wade–Giles: li3 chin4 hai2

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李进; traditional Chinese: 李進; pinyin: Lǐ Jìn; Wade–Giles: li3 chin4

- ^ Chinese: 李淑蒙; pinyin: Lǐ Shúméng; Wade–Giles: li3 shu2 mêng2

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李云鹤; traditional Chinese: 李雲鶴; pinyin: Lǐ Yúnhè; Wade–Giles: li3 yün2 hê4

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李鹤; traditional Chinese: 李鶴; pinyin: Lǐ Hè; Wade–Giles: li3 hê4

- ^ simplified Chinese: 张淑贞; traditional Chinese: 張淑貞; pinyin: Zhāng Shúzhēn; Wade–Giles: chang shu2 chên

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李云古; traditional Chinese: 李雲古; pinyin: Lǐ Yúngǔ; Wade–Giles: li3 yün2 ku3

- ^ simplified Chinese: 蓝苹; traditional Chinese: 藍蘋; pinyin: Lán Píng; Wade–Giles: lan2 ping2

- ^ simplified Chinese: 李润青; traditional Chinese: 李潤青; pinyin: Lǐ Rùnqīng; Wade–Giles: li3 jun4 ch'ing

- ^ Chinese: 李梓; pinyin: Lǐ Zǐ; Wade–Giles: li3 tzu3

- ^ Chinese: 李德文; pinyin: Lǐ Déwén; Wade–Giles: li3 tê2 wên2

- ^ simplified Chinese: 裴明伦; traditional Chinese: 裴明倫; pinyin: Péi Mínglún; Wade–Giles: p'ei2 ming2 lun2; According to the Revised Mandarin Chinese Dictionary by the Taiwanese Ministry of Education, the surname is pronounced Péi.[29] However, Hong Kong's Multi-function Chinese Character Database notes an additional pronunciation as Féi.[30] Terrill 1999 (pp. 29–31) adopts the translation Fei.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Terrill 1999, p. 10.

- ^ A Great Trial in Chinese History – the Trial of the Lin Biao and Jiang Qing Counter-Revolutionary Cliques, Beijing / Oxford: New World Press/Pergamon Press, 1981, p. title, ISBN 0-08-027918-X

- ^ a b Landsberger, Stefan R. (2008). Madame Mao: Sharing Power with the Chairman. International Museum of Women.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (5 June 1991). "New York Times". Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Ye, Yonglie (14 October 2014). "The rise and fall of the gang of four". Shanghai Observer (in Simplified Chinese). Shanghai: Jiefang Daily.

- ^ "Yu Guangyuan: The Jiang Qing I remember" (in Chinese). Culture.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Lin, Jenny (30 November 2018), "Introduction: Locating global contemporary art in global China", Above sea: Contemporary art, urban culture, and the fashioning of global Shanghai, Manchester University Press, pp. 1–25, doi:10.7765/9781526132611.00009, ISBN 978-1-5261-3261-1, retrieved 27 November 2024

- ^ a b Trebach, Bradford (16 June 1991). "Remember Those Who Almost Changed China; 'Pure and Simple'". New York Times.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 15.

- ^ a b Sisyphus 2015a, p. 33.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 52.

- ^ Lee, Mong-Ping (1967). "Chiang Ching: Mao's Wife and Deputy". Communist Affairs. 5 (3): 19–22. doi:10.1016/0588-8174(67)90051-4. ISSN 0588-8174. JSTOR 45368207.

- ^ Sisyphus 2015a, p. 48.

- ^ a b Sisyphus 2015a, p. 56.

- ^ Shu, Yun (16 May 2020). "江青骨灰11年後方才入土 死後究竟葬於何處?". Jornal San Wa Ou (in Chinese). Macau. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ "Duowei: Jiang Qing's gravesite" (in Chinese). Dwnews.com. 12 January 2009. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Keyser, Catherine H. "Guide to Pronouncing Romanized Chinese (Wade-Giles and Pinyin)". Columbia University. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Carter, James (19 May 2021). "The death of Jiang Qing, a.k.a., Madame Mao". The China Project. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ a b Terrill, Ross (2014). The Life of Madame Mao. New Word City. ISBN 9781612306520.

- ^ Lee, Lily Xiao Hong (1998). 中國婦女傳記詞典: The Twentieth Century, 1912–2000. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765607980.

- ^ a b Sisyphus 2015a, p. 31.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Terrill, Ross (1984). The White-boned Demon: A Biography of Madame Mao Zedong. Morrow. ISBN 9780688024611.

- ^ Butterfield, Fox (4 March 1984). "Butterfield, Fox. "Lust, Revenge, and Revolution". The New York Times. 4 March 1984. Retrieved 10 June 2011. p. 1". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Terrill 1999, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 22.

- ^ a b Terrill 1999, p. 23-29.

- ^ Ministry of Education, R.O.C. (2021). "裴 : ㄆㄟˊ". Revised Mandarin Chinese Dictionary.

- ^ The Chinese University of Hong Kong (2014). "裴". Multi-function Chinese Character Database.

- ^ Terrill 1999, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 33.

- ^ a b Terrill 1999, p. 34.

- ^ Terrill 1999, p. 35.

- ^ a b c "江青赴延安前的风流韵事". Phenix News. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Gao, Yunxiang (2021). Arise, Africa! Roar, China! Black and Chinese Citizens of the World in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 239. ISBN 9781469664606.

- ^ Witke, Roxane (21 March 1977). "Special Section: Comrade Chiang Ch'ing Tells Her Story". Time.

- ^ "Suicide of Jiang Qing, Mao's Widow, Is Reported". New York Times. 15 July 2016 [1991-06-05]. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Liang, Jiagui (30 September 2003). "Jiang Qing: late 1937-1949" (PDF). Twenty-first Century (in Chinese) (18) (Online ed.).

- ^ Li 2023, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Li 2023, p. 227.

- ^ Li 2023, p. 229.

- ^ a b Li 2023, p. 230.

- ^ Li 2023, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b c d Li 2023, p. 231.

- ^ Landsberger, Stefan R. (2024). "Madame Mao". International Museum of Women. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Introduction to the Cultural Revolution". Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ Minami, Kazushi (2024). People's Diplomacy: How Americans and Chinese Transformed US-China Relations during the Cold War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501774157.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (18 December 2020). "Uncovering the Cultural Revolution's Awful Truths". The Atlantic. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Hsin, Chi (1977). The Case of the Gang of Four: With First Translation of Teng Hsiao-Ping's Three Poisonous Weeds. Cosmos Books, Ltd. p. 19. ASIN B000OLUOE2.

- ^ Chang, Jung; Halliday, Jon (2006). Mao: The Unknown Story. Anchor. p. 864. ISBN 0-679-74632-3.

- ^ Joan Chen. aratandculture.com

- ^ Roberts, Rosemary (March 2008). "Performing Gender in Maoist Ballet: Mutual Subversions of Genre and Ideology in The Red Detachment of Women". Intersections.

- ^ Khoua, Choui; Wang, Bin (1950), The White-haired Girl, Qiang Chen, Baiwan Li, Hua Tian, retrieved 7 November 2017

- ^ Winzenburg, John (2016). Musical-Dramatic Experimentation in the Yangbanxi: A Case for Precedence in The Great Wall. US: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 189–212.

- ^ Harris, Kristine (30 August 2010). "Re-makes/Re-models: The Red Detachment of Women between Stage and Screen". Opera Q. 26 (2–3): 316–342. doi:10.1093/oq/kbq015. S2CID 191566356.

- ^ a b c Ludden, Yawen (1 September 2017). "The transformation of Beijing opera: Jiang Qing, Yu Huiyong and yangbanxi". Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art. 4 (2): 143–160. doi:10.1386/jcca.4.2-3.143_1. ISSN 2051-7041.

- ^ a b c d e f Ludden, Yawen (23 January 2013). China's Musical Revolution: From Beijing Opera to Yangbanxi (PhD thesis). Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky. pp. 114–202.

- ^ a b "Jiang Qing (1964): On the Revolution of Peking Opera". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Li 2023, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Teiwes, Frederick C.; Sun, Warren (2004). "The First Tiananmen Incident Revisited: Elite Politics and Crisis Management at the End of the Maoist Era". Pacific Affairs. 77 (2): 211–235 (213). JSTOR 40022499.

- ^ "Jiang Qing wants to be Empress". Dashiw.com. 11 February 2009. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Zheng, Haiping (2010). "The Gang of Four Trial". University of Missouri-Kansas City. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "Pages from Chinese History". Civilwind.com. 8 August 2003. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ "Communist Party History: Memoirs of Jiang Qing on 6 October 1976". Cpc.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Cook, Alexander C. (2016). The Cultural Revolution on Trial: Mao and the Gang of Four. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9780511980411. ISBN 978-0-521-76111-6.

- ^ "Gang of Four trial starts Thursday". UPI. 19 November 1980. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Hutchings, Graham (2001). Modern China. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01240-2.

- ^ "Mao's widow spared". UPI. 25 January 1983. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ MacFarquhar & Schoenhals 2006, p. 455.

- ^ "China confirms suicide of Mao's widow". UPI. 4 June 1991. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ "Madame Mao reported a suicide in Beijing". UPI. 3 June 1991. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ "Duowei: Jiang Qing's gravesite" (in Chinese). Dwnews.com. 12 January 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Salino, Silvia (2021). "Jiang Qing, between Fact and Fiction: The Many Lives of a Revolutionary Icon". ASIEN: The German Journal on Contemporary Asia (158/159): 86–104. ISSN 2701-8431.

- ^ WuDunn, Sheryl (9 July 2000). "Sympathy for the Demon". New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Li, Jie (2023). Cinematic Guerillas: Propaganda, Projectionists, and Audiences in Socialist China. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231206273.

- Li, Zhisui (1996). The private life of Chairman Mao: the memoirs of Mao's personal physician. London: Arrow. ISBN 978-0-09-964881-9.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02748-0.

- Terrill, Ross (1992). Madame Mao, the white-boned demon: a biography of Madame Mao Zedong (Touchstone 1st ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-74484-7.

- Terrill, Ross (1999). Madame Mao: the white boned demon (Revised ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2922-2.

- Witke, Roxane (1977). Comrade Chiang Ch'ing. Boston, MA: Little-Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-94900-2.

- Sisyphus, John, ed. (2015a). When Chiang Ching was in Shanghai: Actress Lan Ping (in Traditional Chinese). New Taipei, Taiwan: Sisyphus Publishing. ISBN 978-986-91545-0-5.

- Zhang, Rong (1991). Wild swans: three daughters of China. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-68546-1.

Further reading

[edit]- A great trial in Chinese history: the trial of the Lin Biao and Jiang Qing counter-revolutionary cliques, Nov. 1980 - Jan. 1981 (1st ed.). Beijing: New World Press. 1981. ISBN 978-0-08-027919-0.

- Sisyphus, John, ed. (2015b). Mao Zedong's Standard Bearer: Chiang Ching and the Cultural Revolution (in Traditional Chinese). Vol. I. New Taipei, Taiwan: Sisyphus Publishing. ISBN 978-986-91545-1-2.

- Sisyphus, John, ed. (2015c). Mao Zedong's Standard Bearer: Chiang Ching and the Cultural Revolution (in Traditional Chinese). Vol. II. New Taipei, Taiwan: Sisyphus Publishing. ISBN 978-986-91545-2-9.

External links

[edit]- Feature on Madame Mao by the International Museum of Women (archived 9 December 2008)

- Jiang Qing's tomb (archived 31 August 2009)

- Hudong.com, Jian Qing Archived 6 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 84-minute documentary film (on-line, in Chinese)

- Jiang, Qing 1914- 1991, Wilson Center Digital Archive

- First ladies of the People's Republic of China

- 1914 births

- 1991 suicides

- 1991 deaths

- 20th-century Chinese actresses

- 20th-century Chinese women politicians

- Actresses from Shandong

- Anti-revisionists

- Chinese actor-politicians

- Chinese Communist Party politicians from Shandong

- Chinese film actresses

- Chinese Maoists

- Chinese Marxists

- Chinese politicians convicted of crimes

- Chinese politicians who died by suicide

- Expelled members of the Chinese Communist Party

- Gang of Four

- Socialist feminists

- Critics of religions

- Chinese atheists

- People with hypochondriasis

- Family of Mao Zedong

- Maoist theorists

- Members of the 10th Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party

- Members of the 9th Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party

- People from Zhucheng

- People with polydactyly

- People's Republic of China politicians from Shandong

- Politicians from Weifang

- Prisoners sentenced to death by the People's Republic of China

- Suicides by hanging in China

- Suicides in the People's Republic of China

- Secretaries to Mao Zedong

- Women Marxists

- Jiang Qing

- Inmates of Qincheng Prison