Spermatogonium

| Spermatogonium [1] | |

|---|---|

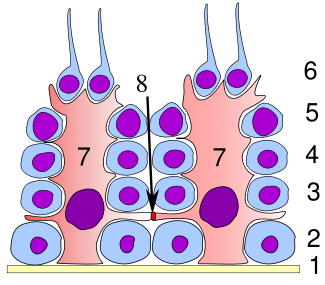

Germinal epithelium of the testicle. 1 basal lamina, 2 spermatogonia, 3 spermatocyte 1st order, 4 spermatocyte 2nd order, 5 spermatid, 6 mature spermatid, 7 Sertoli cell, 8 tight junction (blood testis barrier) | |

Histological section through testicular parenchyma of a boar. 1 Lumen of Tubulus seminiferus contortus, 2 spermatids, 3 spermatocytes, 4 spermatogonia, 5 Sertoli cell, 6 myofibroblasts, 7 Leydig cells, 8 capillaries | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D013093 |

| FMA | 72291 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A spermatogonium (plural: spermatogonia) is an undifferentiated male germ cell. Spermatogonia undergo spermatogenesis to form mature spermatozoa in the seminiferous tubules of the testicles.

There are three subtypes of spermatogonia in humans:

Type A (dark) cells, with dark nuclei. These cells are reserve spermatogonial stem cells which do not usually undergo active mitosis. Type A (pale) cells, with pale nuclei. These are the spermatogonial stem cells that undergo active mitosis. These cells divide to produce Type B cells. Type B cells, which undergo growth and become primary spermatocytes.

Types of spermatogonia

[edit]Spermatogonia are often classified into different types depending on their stage in the differentiation process. In humans and most mammals, spermatogonia are divided into two types, A and B, but this can differ for other organisms. [2]

There are three subtypes of spermatogonia in humans:

- Type A (dark) cells, with dark nuclei. These cells are reserve spermatogonial stem cells which do not usually undergo active mitosis.

- Type A (pale) cells, with pale nuclei. These are the spermatogonial stem cells that undergo active mitosis. These cells divide to produce Type B cells.

- Type B cells, which undergo growth and become primary spermatocytes.

Spermatogenesis

[edit]Spermatogenesis is the process in which sperm cells are produced and formed into mature spermatozoa from spermatogonia. Males mature spermatozoa (sperm) are produced to later join with a female oocyte (egg) to create offspring. Throughout the process of spermatogenesis, there are many different parts of the male anatomy, accessory organs, and hormones. However, spermatogenesis can be broken down in the following steps, which are initiated at the start of puberty:

- Spermatogenesis occurs in the germinal epithelium of the seminiferous tubules. Spermatogonia undergo meiosis to produce spermatids that later mature into spermatozoa. The spermatogonia duplicate their DNA to obtain 46 chromosomes in preparation for the primary division. At this stage, the germ cells are now referred to as primary spermatocytes. [3]

- The primary spermatocytes undergo a primary division, yielding two secondary spermatocytes each with 23 chromatids. The secondary spermatocytes then undergo a second division to produce two spermatids, each with 23 chromosomes. [3]

- The spermatids are currently surrounded by Sertoli cells, which nourish the sperm and produce inhibin, an inhibitor of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).[3]

- The last step of spermatogenesis is spermiogenesis. During this process, the spermatids are transformed into spermatozoa, mature sperm. At this point, no other division occurs. The sperm is released from the Sertoli cells and transported to the epididymis through peristalsis. While in the epididymis, the sperm is stored and begins maturation. Once the sperm has fully matured, it will reach its spermatozoan phase.[3]

Male hormones

[edit]Spermatogenesis is a very regulated process controlled by endocrine stimuli. These stimuli include the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and the luteinizing hormone (LH), which stimulate testosterone. These hormones produce regulatory signals that control the maintenance and nutrients needed for the developing germ cells. The following explains what each hormone contributes to the regulation of spermatogenesis.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH): Secreted by the hypothalamus, GnRH triggers the release of the luteinizing hormone (LH)]] and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). [4]

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): FSH is in charge of stimulating Sertoli cells with testosterone to produce regulatory molecules and nutrients needed for the cells. The nutrients are a needed factor for the maintenance of spermatogenesis.[5]

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH)]]: LH stimulates Leydig cells to produce testosterone.[4]

- Testosterone: Testosterone is an important hormone that helps mature sperm through the process and gives rise to male secondary characteristics.[4]

- Inhibin: Inhibin is secreted by Sertoli cells. It participates in regulating and inhibiting FSH. [6]

Sperm structure

[edit]The overall structure of spermatozoa is very specialized as the cell has fully differentiated and matured. As spermatozoa, the cell no longer undergoes division. It consists of a head, midpiece, and flagella tail for motility.

- Head: As the head of the sperm, it is an ovular shape consisting of the nucleus and the acrosome.[4]

- Acrosome: The Acrosome covers two-thirds the head’s outside area; it contains hydrolytic enzymes needed to penetrate the oocyte for fertilization.[4]

- Nucleus: The nucleus consists of conjugated DNA with proteins. The chromatin is tightly compacted with no visible chromosomes.[4]

- Midpiece/ Neck: The midpiece consists of the mitochondria where ATP is produced.[4]

- Tail: The tail consists of a long flagellum made up of microtubules. It arises during the spermatid stage and allows motility.[4]

Infertility

[edit]Infertility is the inability of a couple to conceive an offspring after a year of unprotected intercourse. Spermatogonia plays a vital role in male fertility, as they are the initial germ cells for sperm production. A disruption of spermatogonia’s function, structure, or development can lead to infertility. There are several factors that can affect spermatogenesis and the health of spermatogonia, including genetic disorders, hormonal imbalances, environmental factors, and many more.[7]

Diseases That Cause Infertility

[edit]There are many diseases and causes of infertility experienced in males.

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a genetic cognition that changes proteins in the body. It causes mucus to become thick and sticky leading to blockages and damage as it builds up.[8]

- The vast majority of Men with cystic fibrosis suffer from infertility issues. The main cause of infertility is due to obstructive azoospermia (OA). OA is a condition where there is a blockage in a male's reproductive tract, resulting in a lack of sperm in a male's ejaculate. This is mostly due to an absence of the vas deferens, which is thought to be caused by CFTR mutations. In most males with CF, spermatogenesis does occur, but the males have a lower ejaculate volume. [9]

- Klinefelter's Syndrome

- Klinefelter's is the most common chromosomal abnormality associated with male infertility. Klinefelter's is due to a trisomy of XXY on the 23rd chromosome, giving males an extra X chromosome. The cause of infertility is related to the replacement of normal testicular architecture with tubular atrophy, sclerosis, or maturation arrest, which degenerates into fibrosis. [10]

Cystic Fibrosis and Klinefelter's Syndrome are just two examples of ways diseases and genetic mutations can lead to infertility in men.

Anticancer drugs

[edit]Anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin and vincristine can adversely affect male fertility by damaging the DNA of proliferative spermatogonial stem cells. Experimental exposure of rat undifferentiated spermatogonia to doxorubicin and vincristine indicated that these cells are able to respond to DNA damage by increasing their expression of DNA repair genes, and that this response likely partially prevents DNA break accumulation.[11] In addition to a DNA repair response, exposure of spermatogonia to doxorubicin can also induce programmed cell death (apoptosis).[12]

Additional images

[edit]-

Schematic diagram of Spermatocytogenesis Wandimu Geneti

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mahla, R.S. (2012). "Spermatogonial Stem Cells (SSCs) in Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) Testis". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e36020. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736020M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036020. PMC 3334991. PMID 22536454.

- ^ Waheeb, R.; Hofmann, M.-C. (2011-08). "Human spermatogonial stem cells: a possible origin for spermatocytic seminoma". International Journal of Andrology. 34 (4 Pt 2): e296–305, discussion e305. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01199.x. ISSN 1365-2605. PMC 3146023. PMID 21790653.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d "Spermatogenesis". Default. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sharma, Rakesh; Agarwal, Ashok (2011), Zini, Armand; Agarwal, Ashok (eds.), "Spermatogenesis: An Overview", Sperm Chromatin: Biological and Clinical Applications in Male Infertility and Assisted Reproduction, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 19–44, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-6857-9_2, ISBN 978-1-4419-6857-9, retrieved 2024-12-04

- ^ Oduwole, Olayiwola O.; Peltoketo, Hellevi; Huhtaniemi, Ilpo T. (2018-12-14). "Role of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone in Spermatogenesis". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 9. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00763. ISSN 1664-2392.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Suede, Samah H.; Malik, Ahmad; Sapra, Amit (2024), "Histology, Spermatogenesis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31985935, retrieved 2024-12-04

- ^ Leslie, Stephen W.; Soon-Sutton, Taylor L.; Khan, Moien AB (2024), "Male Infertility", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32965929, retrieved 2024-12-04

- ^ "Cystic Fibrosis - What Is Cystic Fibrosis? | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 2024-11-15. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ Naz Khan, Farah; Mason, Kelly; H Roe, Andrea; Tangpricha, Vin (Dec 6, 2021). "CF and male health: Sexual and reproductive health, hypogonadism, and fertility". Naz Khan F, Mason K, Roe AH, Tangpricha V. CF and male health: Sexual and reproductive health, hypogonadism, and fertility. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021 Dec 6;27:100288. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100288. PMID: 34987977; PMCID: PMC8695349.

- ^ Hawksworth DJ, Szafran AA, Jordan PW, Dobs AS, Herati AS. Infertility in Patients With Klinefelter Syndrome: Optimal Timing for Sperm and Testicular Tissue Cryopreservation. Rev Urol. 2018;20(2):56-62. doi: 10.3909/riu0790. PMID: 30288141; PMCID: PMC6168324.

- ^ Beaud H, van Pelt A, Delbes G (2017). "Doxorubicin and vincristine affect undifferentiated rat spermatogonia". Reproduction. 153 (6): 725–735. doi:10.1530/REP-17-0005. PMID 28258155.

- ^ Habas K, Anderson D, Brinkworth MH (2017). "Germ cell responses to doxorubicin exposure in vitro" (PDF). Toxicol. Lett. 265: 70–76. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.016. hdl:10454/10685. PMID 27890809.