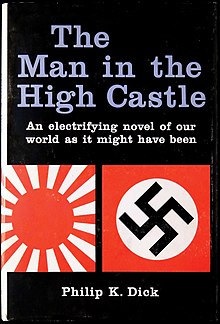

The Man in the High Castle

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Philip K. Dick |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | alternative history, science fiction, philosophical fiction |

| Publisher | Putnam |

Publication date | October 1962 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 240 |

| OCLC | 145507009 |

| 813.54 | |

The Man in the High Castle is an alternative history novel by Philip K. Dick, first published in 1962, which imagines a world in which the Axis Powers won World War II. The story occurs in 1962, fifteen years after the end of the war in 1947, and depicts the life of several characters living under Imperial Japan or Nazi Germany as they rule a partitioned United States. The eponymous character is the mysterious author of a novel-within-the-novel entitled The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, a subversive alternative history of the war in which the Allied Powers are victorious.

Dick's thematic inspirations include the alternative history of the American Civil War, Bring the Jubilee (1953), by Ward Moore, and the I Ching, a Chinese book of divination that features in the story and the actions of the characters. The Man in the High Castle won the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1963, and was adapted to television for Amazon Prime Video as The Man in the High Castle in 2015.

Synopsis

[edit]Background

[edit]

In the alternative history imagined in The Man in the High Castle, Giuseppe Zangara assassinates President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, resulting in the continuation of the Great Depression and the policy of United States non-interventionism at the start of World War II in 1939. American inaction allows Nazi Germany to conquer and annex continental Europe and the Soviet Union into the Reich. The exterminations of the Jews, the Romani, the Bible Students, the Slavs, and all other peoples whom the Nazis considered subhuman ensued. The Axis powers then jointly conquered Africa, and still compete for the control of South America in 1962.[1] Imperial Japan won the war in the Pacific and invaded the West Coast of the United States, while Nazi Germany invaded the East Coast; the surrender of the Allies ended World War II in 1947.

By 1962, Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany are the world's superpowers, fighting a geopolitical cold war over the world, and in particular over the former United States and South America. Japan extended the Co-Prosperity Pacific Alliance with the establishment of the Pacific States of America (PSA), with the politically neutral Rocky Mountain States acting as a buffer against the Nazi territory to the east. Nazi North America is composed of two countries: The South, and the northeastern part of the former contiguous United States of America, which is referred to as "the U.S." in the book, both of which are ruled by collaborationist pro-Nazi puppet regimes. Canada remains an independent country.

The aged Adolf Hitler is incapacitated by tertiary syphilis, Martin Bormann is the acting Chancellor of Germany, and many high-ranking Nazi leaders—Joseph Goebbels, Reinhard Heydrich, Hermann Göring, and Arthur Seyss-Inquart—still survive and vie to succeed Hitler as the Führer of the Greater Germanic Reich. Technologically, the Nazis have drained the Mediterranean Sea for Lebensraum and farmland, developed and used the hydrogen bomb, developed rockets for traveling throughout the world and into outer space, and have undertaken colonization missions to the Moon and to the planets Venus and Mars.

Plot

[edit]In 1962, it has been fifteen years since Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany won World War II. In San Francisco, in the Pacific States of America, Japanese judicial racism has enslaved black people and reduced the Chinese residents to second-class citizens. Businessman Robert Childan owns an antique shop there that specializes in Americana for a Japanese clientele who fetishize cultural artifacts of the former United States. One day, Childan receives a request from Nobusuke Tagomi, a high-ranking trade official, who seeks a gift to impress a Swedish industrialist named Baynes. Childan can fulfil Tagomi's request because he is well-stocked with counterfeit antiques made by the metal works Wyndam-Matson Corporation.

Recently fired from his job at a Wyndam-Matson factory, Frank Frink (formerly Fink) is a secret Jew and war veteran who agrees to join a former co-worker to start a business making and selling jewelry. Meanwhile, in the Rocky Mountain States, Frank's ex-wife, Juliana Frink, works as a judo instructor in Canon City, Colorado and, in her private life, has begun a sexual relationship with Joe Cinnadella, an Italian truck driver and ex-soldier.

Frink blackmails the Wyndam-Matson Corporation for money to finance his jewelry business, threatening to expose their supplying counterfeit antiques to Childan. Tagomi and Baynes meet, but Baynes repeatedly delays conducting any real business because he awaits a third party from Japan. The Nazi news media announces that Chancellor of Nazi Germany Martin Bormann has died after a short illness. Childan takes some of Frink's "authentic metalwork" jewelry on consignment in order to curry favor with a Japanese client, who, to Childan's surprise, says it possesses much Wu, spiritual awareness. Juliana and Joe travel by road to Denver, Colorado, but en route Joe impulsively decides that they take a side trip to Cheyenne, Wyoming, to meet Hawthorne Abendsen, the mysterious author of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, a novel of speculative fiction that presents an alternate history of World War II wherein the Allies defeat the Axis. The Nazis banned the book in the U.S., but the Japanese allow its publication and sale in the Pacific States of America. Supposedly, Abendsen lives in a heavily guarded estate named the High Castle. Meanwhile, the Nazi news media inform the public that Joseph Goebbels is the new Chancellor of Nazi Germany.

After much delay, Baynes and Tagomi meet their Japanese contact, while the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the Nazi security service, is close to arresting Baynes, who is actually Nazi defector Rudolf Wegener. Baynes warns his contact, a Japanese general, of the existence of Operation Dandelion, a plan of Goebbels for a Nazi sneak attack upon the Japanese Home Islands, with the goal of destroying the Empire of Japan. Frink is exposed as a crypto-Jew and arrested by the San Francisco police. Elsewhere, two SD agents confront Baynes and Tagomi, who uses his antique American pistol to kill both agents. In Colorado, Joe changes his appearance and mannerisms before the side trip to the High Castle in Wyoming; Juliana infers that Joe intends to assassinate Abendsen. Joe reveals himself to be a Swiss Nazi when he confirms his intention; Juliana kills Joe and goes to warn Abendsen.

Wegener flies back to Germany and learns that Reinhard Heydrich (a member of the faction against Operation Dandelion) has launched a coup d'état against Goebbels, to install himself as Chancellor of Nazi Germany. Tagomi is shocked by having killed the SD agents and goes to the antiques shop to sell the pistol back to Childan; instead, sensing the spiritual energy from one of Frink's jewelry creations, Tagomi buys the jewelry. Tagomi then undergoes an intense spiritual experience during which he momentarily perceives an alternative version of San Francisco, evidenced by the Embarcadero freeway, which he has never seen and by the fact that white people do not defer to Japanese people.

Tagomi later meets with the German consul in San Francisco and compels the Germans to free Frink, whom Tagomi has never met, by refusing to sign the order of extradition to Nazi Germany. Juliana has a spiritual experience when she arrives in Cheyenne. She discovers that Abendsen lives with his family in a normal house, having abandoned the High Castle because of a changed outlook on life; thus the possibility of being assassinated no longer worries him. After evading Juliana's questions about his literary inspiration, Abendsen says he used the I Ching, a Chinese book of divination, to guide the writing of his novel. Before leaving, Juliana infers then that Truth wrote the novel to reveal the Inner Truth that Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany did lose World War II in 1945.

The Grasshopper Lies Heavy

[edit]Several characters in The Man in the High Castle read the popular novel The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, by Hawthorne Abendsen, the title of which the readers presume derives from the Bible verse fragment: "The grasshopper shall be a burden" (Ecclesiastes 12:5). As an alternative history of the Second World War, wherein the Allies defeat the Axis Powers, the Nazi regime bans The Grasshopper Lies Heavy in the South, whereas the Pacific States of America allow the publication and sale of the counterfactual novel.[2]: 91

The Grasshopper Lies Heavy postulates that President Roosevelt survives the 1933 assassination attempt but chooses not to seek re-election in 1940. The next president, Rexford Tugwell, moves the American Pacific Fleet from Pearl Harbor, saving it from attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy, which ensures that the country is better equipped to fight the war.[2]: 70 Having retained most of their military-industrial capabilities, the United Kingdom contributes more to the Allied war effort, which facilitates the defeat of Erwin Rommel in the North African Campaign. The British fight the Axis armies through the Caucasus to join the Soviet Union and defeat the Nazis in the Battle of Stalingrad; the Kingdom of Italy reneges its membership in the Axis and betrays the Nazis; the British Army joins the Red Army in the Battle of Berlin, the decisive defeat of Nazi Germany. At war's end in 1945, Hitler and the Nazi leaders are tried as war criminals and are put to death,[2]: 131 with Hitler's last words being Deutsche, hier steh' ich ("Germans, here I stand"), in imitation of Martin Luther.

After the war, Tugwell promulgates the New Deal for the countries of the world, which finances a decade of rebuilding in China and the education of illiterate peoples in the undeveloped countries of Africa and Asia, who receive television sets by which they are taught to read and write, are instructed in digging wells and in purifying water. The New Deal financial assistance facilitates American businesses building factories in the undeveloped countries of Asia and Africa. American society is peaceful and harmonious and is at peace with the other countries of the world; the war ends the Soviet Union. Ten years after the war, still headed by Winston Churchill, the British Empire becomes militaristic, anti-American and establishes prison camps in India for Chinese subjects considered disloyal. Suspecting that the United States is sponsoring the anti-colonial subversion of British colonial rule in Asia, Churchill provokes a cold war for global hegemony; the geopolitical rivalry leads to an Anglo-American war won by the United Kingdom.[2]: 169–172

Inspirations

[edit]Dick said that he imagined the story of The Man in the High Castle (1962) from his reading of the novel Bring the Jubilee (1953), by Ward Moore, which is an alternative history of the U.S. civil war won by the Confederacy. In the acknowledgements page of The Man in the High Castle, Dick mentions the thematic influences of the popular history The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (1960), by William L. Shirer; the biography Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952), by Alan Bullock; The Goebbels Diaries (1948); Foxes of the Desert (1960), by Paul Carrell; and the 1950 translation of the I Ching, by Richard Wilhelm.[3][2] As a novelist, Dick used the I Ching to craft the themes, plot and story of The Man in the High Castle, whose characters also use the I Ching to inform and guide their decisions.[3]

Dick cites the thematic influences of Japanese and Tibetan poetry upon the narrative of The Man in the High Castle; (i) The haiku in page 48 of the novel is from the first volume of the Anthology of Japanese Literature (1955), edited by Donald Keene; (ii) the waka poem in page 135 is from Zen and Japanese Culture (1955), by D. T. Suzuki and (iii) the Tibetan book of the dead, the Bardo Thodol (1960), edited by Walter Evans-Wentz and mentions the sociologic influences of the expressionist novella Miss Lonelyhearts (1933), by Nathanael West, in which an unhappy newspaper reporter pseudonymously writes the "Miss Lonelyhearts" advice column, through which he dispenses advice to emotionally forlorn readers during the Great Depression. Despite his job as Miss Lonelyhearts, the reporter seeks consolation in religion, sexual promiscuity, rural vacations and much work; no activity provides him with a sense of personal authenticity derived from his intellectual and emotional engagement with the world.[2]: 118

Reception

[edit]Avram Davidson praised the novel as a "superior work of fiction", citing Dick's use of the I Ching as "fascinating". Davidson concluded that "It's all here—extrapolation, suspense, action, art, philosophy, plot, [and] character".[4] The Man in the High Castle secured for Dick the 1963 Hugo Award for Best Novel.[5][6][7] In a review of a paperback reprint of the novel, Robert Silverberg wrote in Amazing Stories magazine, "Dick's prose crackles with excitement, his characters are vividly real, his plot is stunning".[8]

In The Religion of Science Fiction, Frederick A. Kreuziger explores the theory of history implied by Dick's creation of the two alternative realities

Neither of the two worlds, however, the revised version of the outcome of WWII nor the fictional account of our present world, is anywhere near similar to the world we are familiar with. But they could be! This is what the book is about. The book argues that this world, described twice, although differently each time, is exactly the world we know and are familiar with. Indeed, it is the only world we know: the world of chance, luck, fate.[9]

In her introduction to the Folio Society edition of the novel, Ursula K. Le Guin writes that The Man in the High Castle "may be the first, big lasting contribution science fiction made to American literature."[10]

Adaptations

[edit]Audiobook

[edit]An unabridged The Man in the High Castle audiobook, read by George Guidall and running approximately 9.5 hours over seven audio cassettes, was released in 1997.[11] Another unabridged audiobook version was released in 2008 by Blackstone Audio, read by Tom Wyner (credited as Tom Weiner) and running approximately 8.5 hours over seven CDs.[12][13] A third unabridged audiobook recording was released in 2014 by Brilliance Audio, read by Jeff Cummings with a running time of 9 hours 58 minutes.[14]

Television

[edit]After a number of attempts to adapt the book to the screen, in October 2014, Amazon's film production unit began filming the pilot episode of The Man in the High Castle in Roslyn, Washington, for release through the Amazon Prime Web video streaming service.[15][16] The pilot episode was released by Amazon Studios on January 15, 2015,[17][18] and was Amazon's "most watched pilot ever" according to Amazon Studios' vice president, Roy Price.[19] On February 18, 2015, Amazon green-lit the series.[20] The show became available for streaming on November 20, 2015.[21]

Incomplete sequel

[edit]In a 1976 interview, Dick said he planned to write a sequel novel to The Man in the High Castle: "And so there's no real ending on it. I like to regard it as an open ending. It will segue into a sequel sometime."[22] Dick said that he had "started several times to write a sequel" but progressed little, because he was too disturbed by his original research for The Man in the High Castle and could not mentally bear "to go back and read about Nazis again".[23] He suggested that the sequel would be a collaboration with another author:

Somebody would have to come in and help me do a sequel to it. Someone who had the stomach for the stamina to think along those lines, to get into the head; if you're going to start writing about Reinhard Heydrich, for instance, you have to get into his face. Can you imagine getting into Reinhard Heydrich's face?[23]

Two chapters of the proposed sequel were published in The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick, a collection of his essays and other writings.[24] Eventually, Dick admitted that the proposed sequel became an unrelated novel, The Ganymede Takeover, co-written with Ray Nelson (known for writing the short story "Eight O'Clock in the Morning" filmed as They Live).

Dick's novel Radio Free Albemuth is rumored to have started as a sequel to The Man in the High Castle.[25] Dick described the plot of this early version of Radio Free Albemuth—then titled VALISystem A—writing:

... a divine and loving ETI [extraterrestrial intelligence] ... help[s] Hawthorne Abendsen, the protagonist-author in [The Man in the High Castle], continue on in his difficult life after the Nazi secret police finally got to him ... VALISystem A, located in deep space, sees to it that nothing can prevent Abendsen from finishing his novel.[25]

The novel eventually became a new story unrelated to The Man in the High Castle.[25] Dick ultimately abandoned the Albemuth book, unpublished during his lifetime, though portions were salvaged and used for 1981's VALIS.[25] Radio Free Albemuth was published in 1985, three years after Dick's death.[26]

See also

[edit]- Fatherland (novel)

- Hypothetical Axis victory in World War II

- Turning Point: Fall of Liberty

- Wolfenstein: The New Order

References

[edit]- ^ The events of the book take place in 1962: in chapter 6, in reference to the killing of Joe Cinadella’s brothers in 1944, Juliana says « But it’s been — eighteen years ».

- ^ a b c d e f Dick, Philip K. (2011). The Man in the High Castle (1st Mariner Books ed.). Boston: Mariner Books. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-547-60120-5. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Cover, Arthur Byron (February 1974). "Interview with Philip K. Dick". Vertex. 1 (6). Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Davidson, Avram (June 1963). "Books". The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction: 61.

- ^ "Philip K. Dick, Won Awards For Science-Fiction Works". The New York Times. March 3, 1982. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "1963 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Wyatt, Fred (November 7, 1963). "A Brisk Bathrobe Canter At Cry Of 'Fire!' Stirs Blood". I-J Reporter's Notebook. Daily Independent Journal. San Rafael, California. Retrieved October 25, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

Belatedly I learned that Philip K. Dick of Point Reyes Station won the Hugo, the 21st World Science Fiction Convention Annual Achievement Award for the best novel of 1962.

- ^ Silverberg, Robert (June 1964). "The Spectroscope". Amazing Stories. 38 (6): 124. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Kreuziger, Frederick A. (1986). In The Religion of Science Fiction. Popular Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780879723675. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

man in the high castle cynical.

- ^ Dick, Philip K. (2015). The Man in the High Castle. London: Folio Society.

- ^ Willis, Jesse (May 29, 2003). "Review of The Man In The High Castle by Philip K. Dick". SFFaudio. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ "The Man in the High Castle". BlackstoneAudio.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ L.B. "Audiobook review: The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, read by Tom Weiner". audiofilemagazine.com. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ The Man in the High Castle. Audible, Inc.

- ^ Muir, Pat (October 5, 2014). "Roslyn hopes new TV show brings 15 more minutes of fame". Yakima Herald. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (July 24, 2014). "Amazon Studios Adds Drama 'The Man In The High Castle', Comedy 'Just Add Magic' To Pilot Slate". Deadline. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "The Man in the High Castle: Season 1, Episode 1". Amazon. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "The Man in the High Castle". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Lewis, Hilary (February 18, 2015). "Amazon Orders 5 New Series Including 'Man in the High Castle'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Robertson, Adi (February 18, 2015). "Amazon green-lights The Man in the High Castle TV series". The Verge. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Moylan, Brian (November 18, 2015). "Does The Man in the High Castle prove that the best TV is now streamed?". The Guardian. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ "Hour 25: A Talk With Philip K. Dick « Philip K. Dick Fan Site". Philipkdickfans.com. June 26, 1976. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ a b RC, Lord (2006). Pink Beam: A Philip K. Dick Companion (1st ed.). Ward, Colorado: Ganymedean Slime Mold Pubs. p. 106. ISBN 9781430324379. Retrieved December 10, 2015.[self-published source]

- ^ Dick, Philip K. (1995). "Part 3. Works Related to 'The Man in the High Castle' and its Proposed Sequel". In Sutin, Lawrence (ed.). The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick: Selected Literary and Philosophical Writings. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-679-74787-7.

- ^ a b c d Pfarrer, Tony. "A Possible Man in the High Castle Sequel?". Willis E. Howard, III Home Page. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ LC Online Catalog — Item Information (Full Record). Catalog.loc.gov. 1985. ISBN 9780877957621. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, William Lansing. 2006. "alternative Histories: Power, Politics, and Paranoia in Philip Roth's The Plot against America and Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle", The Image of Power in Literature, Media, and Society: Selected Papers, 2006 Conference, Society for the Interdisciplinary Study of Social Imagery. Wright, Will; Kaplan, Steven (eds.); Pueblo, CO: Society for the Interdisciplinary Study of Social Imagery, Colorado State University-Pueblo; pp. 107–11.

- Campbell, Laura E. 1992. "Dickian Time in The Man in the High Castle", Extrapolation, 33: 3, pp. 190–201.

- Carter, Cassie, 1995. "The Metacolonization of Dick's The Man in the High Castle: Mimicry, Parasitism and Americanism in the PSA", Science Fiction Studies #67, 22:3, pp. 333–342.

- DiTommaso, Lorenzo, 1999. "Redemption in Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle", Science Fiction Studies # 77, 26:, pp. 91–119, DePauw University.

- Fofi, Goffredo 1997. "Postfazione", Philip K. Dick, La Svastica sul Sole, Roma, Fanucci, pp. 391–5.

- Hayles, N. Katherine 1983. "Metaphysics and Metafiction in The Man in the High Castle", Philip K. Dick. Greenberg, M.H.; Olander, J.D. (eds.); New York: Taplinger, 1983, pp. 53–71.

- Malmgren, Carl D. 1980. "Philip Dick's The Man in the High Castle and the Nature of Science Fictional Worlds", Bridges to Science Fiction. Slusser, George E.; Guffey, George R.; Rose, Mark (eds.); Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, pp. 120–30.

- Mountfort, Paul 2016. "The I Ching and Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle", Science-Fiction Studies # 129, 43:, pp. 287–309.

- Pagetti, Carlo, 2001a. "La svastica americana" [Introduction], Philip K. Dick, L'uomo nell'alto castello, Roma: Fanucci, pp. 7–26.

- Proietti, Salvatore, 1989. "The Man in The High Castle: politica e metaromanzo", Il sogno dei simulacri. Pagetti, Carlo; Viviani, Gianfranco (eds.); Milano: Nord, 1989 pp. 34–41.

- Rieder, John 1988. "The Metafictive World of The Man in the High Castle: Hermeneutics, Ethics, and Political Ideology", Science-Fiction Studies # 45, 15.2: 214–25.

- Rossi, Umberto, 2000. "All Around the High Castle: Narrative Voices and Fictional Visions in Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle", Telling the Stories of America — History, Literature and the Arts — Proceedings of the 14th AISNA Biennial conference (Pescara, 1997), Clericuzio, A.; Goldoni, Annalisa; Mariani, Andrea (eds.); Roma: Nuova Arnica, pp. 474–83.

- Simons, John L. 1985. "The Power of Small Things in Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle". The Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, 39:4, pp. 261–75.

- Warrick, Patricia, 1992. "The Encounter of Taoism and Fascism in The Man in the High Castle", On Philip K. Dick, Mullen et al. (eds.); Terre Haute and Greencastle: SF-TH Inc. 1992, pp. 27–52.

External links

[edit]- The Man in the High Castle title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- The Man in the High Castle cover art gallery

- The Man in the High Castle at the Internet Book List

- The Man in the High Castle at Worlds Without End

- 1962 American novels

- 1962 science fiction novels

- Fiction set in 1962

- Novels set in the 1960s

- American alternate history novels

- Dystopian novels

- Hugo Award for Best Novel–winning works

- Metafictional novels

- Postmodern novels

- Novels by Philip K. Dick

- Novels set in California

- Novels set in San Francisco

- Novels about World War II alternate histories

- G. P. Putnam's Sons books

- American novels adapted into television shows

- Alternate Nazi Germany novels

- Novels set in fictional countries